Films reviewed:

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Asteroid City (2023)

![]() The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014)

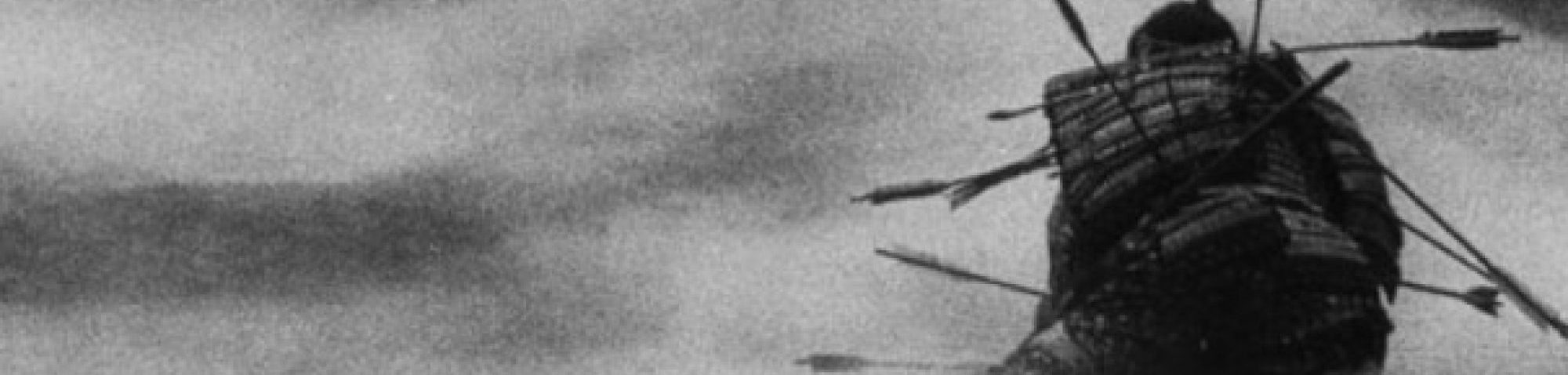

At once his lightest, most whimsical frolic of a movie, and the one dealing with his most difficult, mature themes yet, Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel took his world-creating ploys to new elaborate heights. A flamboyant lothario, a mythically opulent hotel, a not-altogether-unpreposterous murder mystery plot that rides along as fast as Willem Dafoe on skis, all this serves up delights that go down a treat much the same as Mendl’s famed pastries. But look again, and simultaneously in the very same film is Anderson engaging with war and the most horrible side of humanity for the first time, making not only young upcoming lobby-boy Zero an immigrant orphaned by man’s violent cruelty but Ralph Fiennes’ Gustave too. All this is revealed in an understated way, and neither this film nor Anderson have been credited enough for their subtlety.

And what of the painfully melancholy way in which the narration of the now middle-aged Zero (F. Murray Abraham again, in one of the film’s several Russian doll style layers, each with its own aspect ratio) simply skips over the most traumatic event of his life, the death of his beloved, in one brief sentence? All along we thought we had been watching the story recounting the most important and formative events of his life, but in fact not so at all, for that story is too heavy on his heart to tell. Wes Anderson had always fitted in plenty of emotional truths on the bitter-sweetness of life under the seemingly lighter surface of his movies, but here he stretched both poles of that spectrum to new limits. Of course though, the film’s greatest revelation is Ralph Fiennes as outstanding comic actor, and his not even being nominated at the Oscars is just another in a long line of travesties that discredit that awards ceremony from genuine credibility. (January 2015)

![]() Asteroid City (Wes Anderson, 2023)

Asteroid City (Wes Anderson, 2023)

Let me just ‘fess up from the outset: recent Wes Anderson has, for me, become more and more, well, Wes-Andersonian to diminishing returns. I only personally started feeling this way from Isle of Dogs, lamenting the greater balance between twee storybook narratives and emotional truthfulness he so perfectly found on The Royal Tenenbaums or Rushmore.

His latest, Asteroid City, only crystallises my feelings. It is a pastiche of 1950s Cinemascope Eastmancolor desert movies like Bad Day at Black Rock and of Cold War era sci-fi, framed with Wes’s own unmistakable touch and aesthetic. Beyond that touch and that aesthetic, is there really anything out there? This is a movie that seems to huff and puff a lot in attempts at being ‘meaningful’, in asking Big Questions about meaning (the plot literally centres around the question ‘is there anything out there’ in relation to the potential arrival of extraterrestrial beings on Earth), and in using a play-within-a-movie framing device. More than ever before, Wes Anderson is tackling the issue of meaning in his films, this concern that perhaps his movies are not really about anything, and he is tackling this in a very self-reflexive manner. But does this really add something meaningful to Wes’s filmmaking? Call me a skeptic.

At the same time as he is stuck in his own universe, Wes is also increasingly mining the objects of his cinephilic admirations, but only to dig himself deeper in his own hole. References and in-jokes proliferate at a disarming pace. Stories within stories. Frames within frames. Signs within signs. A long list of fine actors reduced to cameos. Clearly, Wes strives for the obsessive universe-building of a Jacques Tati, especially in Playtime (1967), but Tati gave us ample time to democratically choose what to pay attention to in his scenes. It is all very well Wes wanting to play games within every single frame, the way Peter Greenaway does. But what’s the use if it all goes so fast we can barely notice it? And if us trying to notice it takes away from the narrative before, exhausted, we give up? Do all these inter-connections helps us understand something better? The film? The world? Anything? Again, I have doubts.

One of the many little cine-gags Wes has peppered in is the way Jason Schwartzman’s character Augie Steenbeck, an emotionally numb PTSD-suffering war photographer, has shades of the experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton: Augie’s facial hair and some of his photographic compositions vaguely suggest Frampton. But what makes the reference unmistakable is a moment later in the film when Augie burns his hand on an electric grill plate, of the very same kind foregrounded in Frampton’s classic (nostalgia) (1971). Later, the actor playing Augie in the framing device narrative even asks with tormented confusion: “Why does Augie put his hand on the hot grill?”

Why, indeed. Maybe Augie is so emotionally numb he just wants to hurt himself in an inexplicable act of self-destruction to at least feel something. Or maybe the hot grill reference to (nostalgia) is forging an association to that film’s symbolic meaning, where the grill represents time and how it transforms all things. This includes the pent-up grief Augie does not know what to do with, at least until he meets Scarlet Johansson’s Midge Campbell, an equally emotionally wounded Marylin Monroe-esque Hollywood star (come to think of it, there’s also elements of John Huston’s The Misfits, famously Monroe’s last film, in this). But even if the (nostalgia) reference is in there for that reason, for Asteroid City to ‘borrow’ meaning from such a profound film as Frampton’s, how can it possibly connect when the pace turns it into a blink-and-you-miss-it moment?

If these are some of the frustrations of Asteroid City, it should also be said that anyone who watches Wes Anderson for a purely stylistic rollercoaster ride will get more than their money’s worth. Visuals and mise-en-scene are stunning, painting a postcard setting to all the inchoate narrative beats. I have not even mentioned that at heart the film is, if anything (and oh boy, is it many things), a paean to the idealism of youth — but, ask me, Wes did this much better in Moonrise Kingdom. In the end, it is the young stargazers, the whiz-kid children of these numbed and damaged adults, who pick up the pieces. They are curious, fiercely smart, willing to protect science and knowledge from being co-opted for hostile ends*, willing to stand up against the excesses of authority even if that means the US Government, and are so good at looking for signs and clues that they might well be able to figure out what Asteroid City itself is all about. Without their genius, Asteroid City appears to be a movie in search of its own meaning. (July 2023)

*I cannot help but mentally pair Asteroid City with Oppenheimer, a film directed by another mega-auteur with the cachet to create his own universe on his own terms without bending to mainstream directives, and (though I am yet to see it) perhaps another film that deals in its own way with mid-century USA’s relationship with science, technology, power, death, and hope.