Only took 75 years, but here is my Top 20 list for 1947.

20. T-Men (Anthony Mann)

As the old auteurist cliché goes, great directors elevate banal material into something superior onscreen. This is a perfect example of the truth in the cliché. T-Men begins as a B-movie docu-drama on the enforcement agents of the United States Treasury Department (the so-called T-men), with a direct-to-camera introduction by Elmer Lincoln Irey, none other than the real-life ‘T-man’ who brought Al Capone to court on tax evasion charges. Irey’s tone preps us for what we can only expect to be a puff piece glorifying the T-men, and soon a monotone voiceover runs over the fictional retelling of a real case of undercover T-Men versus a counterfeiting ring. But watch on and you’ll see Anthony Mann’s direction and John Alton’s cinematography undermine these more officious intentions at every step.

Irey and the voiceover may speak with presumed authority, but nothing else backs up that steadiness. The camera is always tilted, or too high or too low, decentring all characters including the T-men themselves, as if nobody is in control of this seedy underworld of crime and corruption. The lighting is an extravaganza of expressionistic effects, a choreography of shadows and obliquely-angled flashes of light, of faces peeking in from the darkness, which along with Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946) essentially defined the film noir aesthetic. Irey’s intro may pontificate about the “six fingers on the fist” of the USTD, but for the rest of the movie the two undercover T-men infiltrating the counterfeiting ring are conflicted characters, cornered animals who in order to survive within a criminal jungle are forced to behave like the lawbreakers they are meant to arrest.

Further at odds with the matter-of-fact narration is the way the rogues’ gallery of criminals are the most vivid and memorable characters here, brought to life by Mann and his cast of character actors in a way that makes all too obvious the film’s fascination with these larger-than-life figures even if they err on the wrong side of the law. Finally, the head of the criminal ring turns out to be a respectable businessman hiding his fraudulent activity behind innocuous antiques dealings — in other words, the real villains are no longer identifiable gangsters or thugs (as they were in 1930s movies) but are now at large within legitimised capitalism.

All this creates a fascinating tension between the film the producers wanted T-Men to be and the far more exciting, baroque noir it was turned into, its resulting form and style completely belying the intended content, and in the process satisfying the desires of post-WW2 audiences for grittier and more cynical portrayals of the harsh and violent side of American street life based on real events and cases.

See also: Boomerang (Elia Kazan) — Elia Kazan directed two pictures in 1947, including the Best Picture Oscar-winner Gentleman’s Agreement, a worthy takedown of antisemitism in the USA starring Gregory Peck as a journalist who pretends to be Jewish in order to feel prejudice first-hand. In my eyes, Kazan’s better film of the year though was Boomerang, a less-lauded but more gripping procedural noir about political corruption. Here too we can see the new interest in real-ness, taking inspiration directly from the newspapers to tell a true crime story with authenticity. Produced by Louis de Rochemont, who had made his career in newsreels, Boomerang is like T-Men proof of how audiences’ habits of war-time newsreel footage shown before movies created in them a desire for greater realism.

19. Driftwood (Allan Dwan)

Also shot by T-Men cinematographer John Alton, but in a completely different register, Driftwood is a portrait of American community, centred around a war orphan played by child star Natalie Wood. The girl had been brought up on an isolated farm and raised by her preacher ‘Grandpappy’ whose teachings of scripture she lapped up and committed to memory. When the old man dies, she is completely alone until a doctor from the rural town of Driftwood finds her by chance in the middle of nowhere and takes her in. Once transplanted into the sleepy titular town, her bible-spouting, anachronistic ways create a culture shock, and thus begins a narrative about an orphaned child forced to stay with cantankerous adults who initially don’t want them — c.f. Cassavetes’ Gloria, Besson’s Leon or even a certain Ozu film to come later down this list.

Not that Driftwood plays out quite like any other film. Where else would you see combined a political intrigue with a despicable mayor trying to get re-elected, a courtroom drama in which the defendant is a canine, a will-they won’t-they romance between the doctor and the local woman he loves, an unsentimental depiction of the tribulations of childhood in the face of adult insensitivity, and a subplot based around a virus spread to humans by squirrel bites? And amidst all that a message of faith in modern science and vaccines, who’d have thought! In Driftwood, somehow co-habiting are the old-timey traditional and hints of new-ness. The old is represented by veteran character-actor Walter Brennan as a pharmacist fond of cracking aphorisms and by Hollywood pioneer director Allan Dwan who by 1947 had already been in the movie business for near 40 years. The new is Natalie Wood, then only 9 years old and with a great albeit tragically curtailed career ahead of her; her child acting is of course Hollywood stylised acting rather than naturalistic, but nobody can deny she was an absolute natural in that mode of acting and her performance is one not to miss. The final blend of all this is an uncategorisable fable full of charm and old-time wisdom.

18. The Upturned Glass (Lawrence Huntington)

Not the last British film noir on this list, but probably the oddest. In this unconventionally structured film, a brooding, moody James Mason (equally moody and brooding in another film to come later on this list) is a brilliant surgeon giving a lecture to a packed auditorium. In front of eager students and interested amateurs, he recounts the story of a fellow doctor he once knew called Michael (played by Mason in flashback so that we assume the surgeon’s story is about himself). As the telling unfolds, we learn of how Michael fell mutually in love with the mother of a young girl saved from blindness by his surgical skills. But as the mother was married, they decided to do the responsible thing and part ways. Later, Michael finds out his lost love died under mysterious circumstances and obsesses over meting out justice upon the one he believes responsible for her death: the woman’s spoilt, jealous sister-in-law (played by Pamela Kellino, Mason’s then-wife, who also co-wrote the screenplay). So Michael murders this sister-in-law in an act he deems morally justifiable; end of story. Cut back to the auditorium, flashback over, lecture over, and the ‘real’ Michael now leaves his audience to get on with his day. But this is only the first third of the film…

We soon realise the story was not in the past and what we saw was not in fact a flashback, but the doctor’s own veiled confession of what he is about to do (it’s psychologically telling that he needs to tell it publicly like a pre-emptive purge of guilt to come). It was his mental rehearsal for the ‘perfect murder’ he has planned to commit this same day. Thus the rest of the film leads us to the murder we thought we’d already witnessed in the flashback, which as you might have guessed does not go quite the same way this time. The memorable denouement takes us deep into this man’s quandary, that of a doctor so jaded by saving life that he believes himself rightfully allowed to take it away. The Upturned Glass is a mix of noir, melodrama and existentialism, an unfairly forgotten film that awaits rediscovery as a vital testament to post-war British cinema’s ability to produce films that were suspenseful, morally complex, and Hitchcockian (even without Hitchcock around).

17. Le Tempestaire (Jean Epstein)

For as long as civilisations have existed, the sea has held a gravitational pull on mankind: it elicits a kind of sacred awe reflected in seafarers’ tales of giant monsters, of mermaids and lost horizons. This was an ancient bond but, come the Industrial Revolution, Thalassa’s mystique has washed off as Modernity has taken hold, as men have moved away from the coasts and into the cities into jobs less dependent on the vagaries of sea and tide. Our modern societies have become rationalised, less receptive to what was once deemed a mysterious, quasi-spiritual phenomenon. A symptom of what Max Weber calls the ‘disenchantment’ of modern man and his era…

And yet, so many films have tried to re-capture this sense of awe before the vastness of the ocean and its waves. Films from Emilio Fernandez’s rags-to-riches morality story La Perla (also 1947), via The Cruel Sea (1972, Khalid Siddiq) about pearl divers in Kuwait, up to the aquatic documentaries of Cousteau and Malle, or the rather tedious but no less sea-obsessed The Big Blue (1988). These, and so many others, have paradoxically beseeched that ancient bond with the modern technology of filmmaking almost synonymous with the 20th century. But no film, at least until Bait and The Lighthouse, dove deeper into nautical folklore than Jean Epstein’s one-of-a-kind Breton docu-drama Le Tempestaire.

Epstein, who worked from the 1920s up until the 1950s, was very much a modern man and a modern filmmaker. But he held in fascination the old traditions and ways of life of communities that still maintained that sacred tie to the sea, even believing those mystical seafarers’ tales. Both before and after WW2, he made a series of vivid, experimental shorts chronicling the sailors and fishermen around the coasts of Brittany, deftly casting a non-judgmental, ethnographic lens on the region’s folk culture and beliefs. Perhaps this connection back into the past, into the pre-modern, was all the more necessary so soon after the systematic and worldwide brutality of WW2… certainly a motif that will recur on this list.

In any case, the remarkable 22-minute long Le Tempestaire was the penultimate film in Epstein’s Breton cycle. It has a simple plot: a young woman, worried sick over her fiancé caught in a fishing boat during a sea storm, recruits the help of an old hermit who is the last surviving ‘tempestaire’, a sort of storm-tamer or wind-whisperer whose skills, according to legend, can calm the most dangerous of seas. In 1947, these folk customs are on the way out, as one brief scene showing radio communication underlines: nobody believes in the old storm-whisperers anymore, it is science and electromagnetic waves which relay shore and sea. But Epstein respects the mystical traditions of this proud people and their timeworn beliefs. When the inconsolable girl convinces the reluctant old man to use his powers to save her fiancé, we are almost reminded of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), where there too desperation leaves no other resort but supernatural measures.

For Epstein, this was also the first film he made post-WW2, following a ban from filmmaking in Occupied France. Not that this painful hiatus tempered any of his vivacity. On the contrary, he demonstrates an infinite curiosity towards everything, the sounds of the wind, the patterns of the surf crashing into rocks, the old Breton superstitions, and constantly experiments with new ways of depicting them. The lovingly captured cinematography and sound relay the movement of the waves, the clouds in the sky, the growling of the storm, the rumbling of the winds. Slow-motion and time-lapse shots, superimpositions and reverse-motion effects. Epstein looks into the sea, the skies, this little corner of Northwest France, as if it was the entire cosmos itself.

16. Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk)

This taut noir packs multitudes in just 80 minutes. It opens in the murky darkness of a room, a scuffle ensues, we see only silhouettes and glimpses of faces but understand a man has been killed, a Jewish man in what soon transpires to be an anti-semitic attack. Up to the police investigator (Robert Young, one of three Roberts in the three main roles) to piece the puzzle together, which leads him to a group of demobilised US soldiers (including Mitchum and Ryan, the two other Roberts). Credit for the source novel goes to Richard Brooks, who also wrote the screenplay for Jules Dassin’s classic prison movie Brute Force and later would himself would become a great director of noirs and true-crime films (especially In Cold Blood from 1967), though in the original book the murdered victim was gay rather than Jewish. The change was of course forced by the Production Code, which allowed no direct mention of homosexuality, but it works for the film nonetheless because the racist hatred shown by the very same men who defeated Nazism sends a troubling reminder that prejudice has not magically disappeared after the war.

That is what makes this movie such a strong piece of work: barely over a year and a half after a nation-defining and morale-boosting victory in WW2, Crossfire has no time for jingoistic back-patting and dares to examine the dark underside of the war’s aftermath. If anti-semitism is still present on American soil and brutally enacted by those very same men who defeated Nazism, then what exactly does that say? And if Mitchum’s line, that “Now the snakes are loose, anybody can get them”, refers to the moral deformities of war reaching back to civilian society, is not Crossfire an early example of a serious look at the effect of PTSD on individual soldiers, even a precursor to films like Taxi Driver and others of the Vietnam War era? And what about Sam Levene’s classic “big peanut” speech, a perfect analogy for the anomie the military found itself in once war was over, once the manic high of killing for survival was gone and it had nothing left to do? Or nothing except maybe gear itself towards more and more wars (Korea, Vietnam, etc…). Like the best noirs of the era, this is not a movie afraid of going against the current of positivity, to act as a warning to those complacently thinking everything was now hunky dory in the USA. Small wonder director Edward Dmytryk, and producer Adrian Scott, would just 4 years later be blacklisted by the McCarthy witch-hunts of the HUAC trials.

15. Les jeux sont faits (Jean Delannoy)

(aka The Chips Are Down, aka Second Chance)

Jean-Paul Sartre, paragon of mid-twentieth century French intellectualism, remains remembered for his existentialist treatises, plays and novels; for turning down a Nobel Prize; or for his political sympathies with anti-colonial terrorism (he is name-checked in Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers, of course). Less well-known is his screenwriting work, which includes this fantasy gem where life, death, and fate are but cosmic jokes.

Set in an alternative version of post-war France in which a totalitarian dictator holds power, the plot centres on aristocratic wife Eve (Micheline Presle) and working-class resistance leader Pierre (Marcello Pagliero) who are coincidentally murdered on the same day, transitioning into the afterlife together. As conceived by Sartre’s script (based on his own play), life post-death is a bureaucratically-organised eternity of being stuck as a ghost on Earth, everyone who’s lived and died amassed together in invisible limbo amid the living, observing them without ever being able to participate.

However, as the slightly dotty auntie working at the post-mortal realm’s reception desk explains, there’s been a hiccup: the books show Eve and Pierre were fated to fall in love but they died before this could happen. Even the guardians of existential destiny allow errors to slip through the net sometimes. A compromise is struck; the pair will have a second chance at life, precisely 24 hours to prove their love to each other. Failure to do so and they’ll end up right back among the phantom dead and this time for good.

Both Eve and Pierre have unresolved business on Earth, so do they agree to this second chance out of genuine feeling for each other (a prerequisite if they are to prove their love and stay alive beyond the 24 hours), or just to have another go at being alive again? Will they win their wager against Death or be drawn apart by their very different class milieus? Is it even worth continuing to live and love under this dictatorship, foregoing your social conscience for the sake of a solipsistic romance? And can Fate really allow a second chance once the dice have already been thrown? Imagine Sartre writing a mix of Groundhog Day with A Matter of Life and Death, and peppering it with this range of philosophical and political questions, and you get a sense of this film’s blend of narrative high-concept with deeper thematic concerns. The ideas triggered by Les jeux sont faits linger in our minds long after its plethora of eccentric characters and visual gags have finished entertaining us. Had it been directed by Carné, Cocteau or even Franju, rather than Delannoy, it might well be hailed among the classics of French cinema today, but for now its fate needs a little rescuing of its own from the limbo of forgotten films.

14. They Made Me a Fugitive (Alberto Cavalcanti)

It’s a rather delightful paradox that during the wartime years, a 40-something Brazilian intellectual named Cavalcanti, who had already travelled the world and dabbled in fields as varied as law, architecture, and avant-garde filmmaking, settled in England and ended up directing the most British of cinematic classics. There was Went the Day Well? (1942) about a quaint English village’s resistance against undercover Nazis, there was the iconic ventriloquist’s dummy episode in the horror omnibus Dead of Night (1945), and there was this: an unabashedly bleak film noir, They Made Me a Fugitive, in 1947. It paved the way for a cycle of hard-hitting Brit noir (Brighton Rock (1948), The Third Man (1949), Night and the City (1950), not to mention several more 1947 entries on this list) that could rival Hollywood while remaining distinctively British culturally.

Watching these films takes us back to a very specific moment in post-war Britain, after the euphoria of V-Day had faded and left a downbeat mood, accentuated by the particularly harsh winter of 1946-47 and an economy still shored up by centralised rationing. British noir sprouted as a logical offshoot of the black market racketeer gangs, commonplace as a means to get around rationing. The so-called ‘spiv’, the petty criminal who hustled and profited from these dealings, was the British equivalent of the Prohibition era gangster, and would have been an instantly recognisable archetype to local audiences.

In They Made me a Fugitive, that most British of ’40s actors Trevor Howard stars as Clem, an unemployed ex-soldier, bitter and resentful about the way society has treated him since the end of war, who falls in with a gang of spivs as a last resort. Clem’s fate slides down a slippery spiral, and before long he finds himself a fugitive (the title sort of gives this part away) on the run from the law. On his outlaw odyssey he meets some strange characters, each a tile within the wider mosaic of British society in moral malaise: most memorably, the wife who lets him have a hot meal in her home in exchange for murdering her husband (himself an alcoholic). Something is badly wrong in this diagnosis of post-war Britain. Even though the malaise is everywhere, the evil is most concentrated within the character of Narcy, the gang’s leader (played by Griffith Jones) who has framed Clem. Between Clem and Narcy, we have a classic opposition of characters which anchors the film right up until its devilishly un-redemptive finale.

Narcy, with a name that sounds a bit like narcissist meets nasty, is a rotten apple without morals nor values. Unlike Clem the ex-soldier, Narcy did not fight in the war but only profiteered from it. Clem may be lost in the existential rubble of post-war society, but he takes a stand (so is not completely anomic or apathetic) against Narcy when it comes to selling ‘sherbet’, or drugs to you and I: “I may be a crook but I’m not that kind of crook” he proclaims with his last shred of self-respect. Like in many American gangster films (think The Godfather), the move of organised crime into the drugs trade symbolises a certain moral corrosion. But here, everything is translated so perfectly to a British context, and while domestic critics at the time found the film sordid and pessimistic, the hard-edged depiction of England after the war as a dog-eat-dog jungle (right up to the brutal final words of the ending) today puts the film very much ahead of more sanitised 1940s cinema.

13. Nightmare Alley (Edmund Goulding)

Of the many noirs made in 1947, quite a few were doozies: the odd Mexico-set Ride the Pink Horse which unusually for a noir is so much about innocence, or the Raymond Chandler adaptation Lady in the Lake entirely filmed in first-person point of view which eventually feels gimmicky, both films incidentally directed by and starring Robert Montgomery. But as noir doozies go, very few films can match the strange uniqueness of Nightmare Alley. Carnies and freaks, fake psychics and unethical psychoanalysts, charlatans and alcoholics all inhabit this film’s dark world where nothing can be trusted except the Tarot cards.

At the centre of it all is Stan Carlisle (Tyrone Power), an ambitious young man working as MC for a touring carnival whose gift of the gab and unquenchable thirst for validation will soon lead him to greater heights and down nightmarish recesses. He is also one of the nastiest, most unscrupulous and irredeemable protagonists 1947 Hollywood could have gotten away with — the only other who comes close is George Sanders’ heartless scoundrel in Albert Lewin’s The Private Affairs of Bel Ami. As a character, however, Carlisle is more complex, more disturbing, and more interesting. Hateable, yet vulnerable, and oh so bitterly flawed. From the opening scenes, when we see him fascinated and appalled by the carnival troupe’s so-called ‘human geek’, a drunkard fallen on such hard times that he allows himself to be an exhibit biting off live chickens’ heads before disgusted but paying customers, we already know: Carlisle’s fate is doomed to end only one way.

It is a fascination which the film’s dark appeal shimmers with. The 1946 source novel was written by William Lindsay Gresham, a writer with his own personal demons who’d end up taking his own life some years later. Nightmare Alley begun for him when first he heard the story of a real-life carnival geek. It so haunted him that he had to write about it to exorcise it from his mind.

Then there’s the similar fascination Tyrone Power felt when he campaigned so eagerly for this part, so utterly against type for him. An extremely popular matinee star, so used to playing the strait-laced swashbuckling hero, Power perhaps could relate to feeling caged and paraded by his studio 20th Century Fox. Privately, he yearned to extend his range as an actor but ultimately was prevented from doing so — the studio felt it would ruin his image and risk his bankability with audiences. Though they finally allowed him to play Carlisle, 20th Century Fox buried the film as they had no real idea what to do with it — studio head Darryl Zanuck even added a redemptive tone-deaf ending (a similar fate to that of Tod Browning’s earlier carnie masterpiece Freaks of course). But never again would Power be allowed to play such a detestable jerk and showcase his acting ability in the same way.

Finally, the fascination is also there for us the audience, looking into this dark twisted mirror of human nature, appalled and fascinated at how low men can fall when they try to reach too high. This is a film now starting to be better known, thanks to restoration and Criterion Collection release, recent renewed interest in Gresham’s life and work, as well as Guillermo Del Toro’s unnecessary remake with Bradley Cooper as Carlisle. Just observe the difference in sources: the 1947 film is an urgent adaptation as faithful as censorship would allow it of Gresham’s shockingly bleak novel published just the year before, and written by an author who’d lived through the personal demons of his protagonist. Del Toro’s version is adapting the film itself rather than the novel, making a post-modern pastiche of the original movie, a third-hand dilution. Step right up and go straight to the original instead, if you dare take a dark walk in the alley of nightmares.

See also: Secret Beyond the Door (Fritz Lang) — Speaking of noir doozies, this Fritz Lang gothic Freudian noir is well worth a watch. This was the era in which psychoanalysis and dime-book Freud were starting to become very fashionable in the US, and while Nightmare Alley is deeply cynical about all that stuff, Lang’s film uses it to mine the internal recesses and mental closets of its strange characters. It involves marriage, murders, and a very weird house full of secrets and rooms decorated to be replicas of famous murder sites — external architecture somehow reflecting the twisted, repressed deliberations of the internal mind. A weird movie indeed.

12. The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (Joseph L. Mankiewicz)

Noir bleakness aside, the most palpable fact of life in 1947 was a desire to go on living, somehow. In the aftermath of the War’s carnage and desolation, evidence of the human faculty for mindless evil and of the fragility of life, what could be more cathartic for cinema-goers than films demonstrating the transcendence of eternal life and love? And so you get a cycle of films about the afterlife, miracles, everlasting love, and angels, including Portrait of Jennie (1948), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), The Bishop’s Wife (1947), The Lost Moment (1947), or outside Hollywood Blithe Spirit (1945) and Les jeux sont fait (1947, see above), and of course: The Ghost and Mrs Muir. All of them in one way or another, whether romantic or gothic or both, were reassuring reminders of permanence in the shadow of the war’s destruction. In the 1990s, Hollywood tried to revive a similar sort of cycle, with questionable results (Ghost (1990), The Preacher’s Wife (1996), Michael (1996), City of Angels (1998), etc.), and now audiences are probably far too cynical for producers to bother trying again, so that much-needed lyricism of 1940s cinema stands apart as irreplicable.

Much like William Dieterle’s Portrait of Jennie , in which Joseph Cotten was a painter infatuated with the ethereal spectre of a girl from another age, here too Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s romance between a mortal and a ghost strives for timelessness through love and art. Set in turn-of-the-century England, Gene Tierney stars as the titular Mrs. Muir, a headstrong young widow determined to do things her own way, no matter the societal restrictions caused by her gender or marital status. She decides to re-settle with her young daughter (Natalie Wood, again: see Driftwood) on the English coast, where she falls in love twice: first, with a peculiarly Gothic house decorated in maritime fare including a creepy painting of a sea captain, and secondly with the ghost of that very same sea captain (incarnated by Rex Harrison) who haunts his former home cantankerously.

There are many pleasures to this film: the chemistry between Harrison’s rough old sea-dog and the more demure but still quirkily independent Tierney — true to Mankiewicz’s passion for language and dialogue, the film’s best gag is when Mrs. Muir, ghost-writing the ghost-captain’s maritime memoirs, is appalled at the language he is dictating to her… All we hear of it is a four-letter twang on the typewriter. There’s the masterwork of lighting effects making the sea captain’s ghost come to life through visual mood-setting. There’s the hauntingly romantic and brooding Bernard Hermann score that goes so hand in hand with the film. And there’s the entire plot strand involving Mrs. Muir’s attempts to get literary recognition as a female writer, in which George Sanders plays (what else) a bounder. There’s so much to enjoy on an emotional, aesthetic and intellectual level here. The themes of physical vs metaphysical love, of a woman’s emancipation, of sacrifice, of literary imagination vs quotidian pragmatism, are all sailing around in there before the film ends on a note of the eternal, with young Natalie Wood engraving her name on a piece of wood which she throws into the sea and which, an old sailor on the beach tells her, will float the ocean for all times…

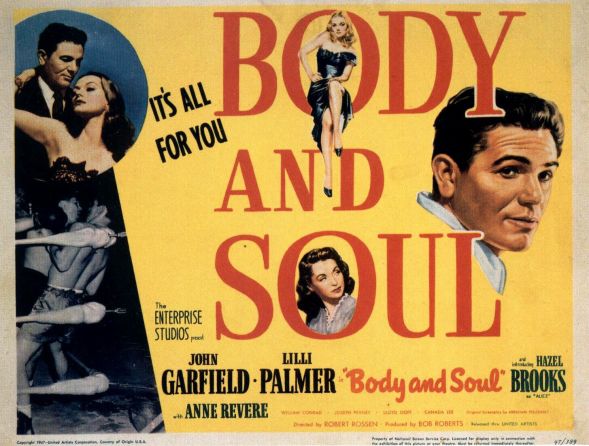

11. Body and Soul (Robert Rossen)

In the wake of WW2, Hollywood produced several punchy noirs centred on boxer protagonists tortured both in and out the ring. The physical and personal pains of these impaired pugilists stood in for the wider moral and economic ills of a corrupt, punch-drunk society hit by one blow too many. On the undercard would be the likes of Kirk Douglas’ ruthless up-and-comer channelling his inner rage into the ring in Champion (1949) or Robert Ryan’s washed-up fatalist in The Set-Up (1949), while main billing belongs to such iconic roles as Burt Lancaster in The Killers (1946), Marlon Brando a few years later in On the Waterfront (1954) or, in Body and Soul, John Garfield’s champ exploited by managers and impresarios, all gangsters milking him for every buck. “I take the beatings and you take the dough,” he exclaims in a moment of bitter self-realisation.

Body and Soul was only Robert Rossen’s second film as director; he’d been a small-time fighter himself as a young man in NYC’s Lower East Side, so he knew the milieu. In hindsight, it’s impossible to watch Garfield’s Faustian descent — from contender to guilt-ridden, cornered animal, only carrion to the sharks circling around him — without thinking of The Hustler (1961), the film that fourteen years later would become Rossen’s masterpiece. There too, a toxic relationship between sportsman (Paul Newman a pool wizard) and agent (George C. Scott at his most Mephistophelian) is the podium for a caustic takedown of the American Dream’s capitalist mirage infiltrating every nook and cranny of society, from sport to friendship to love, polluting every chance of private happiness.

The Hustler of course came after the McCarthy anti-communist witch-hunts of the 1950s where Rossen had to give names, and Abraham Polonsky (screenwriter of Body and Soul and, like Rossen, a left-wing Jewish New Yorker) pleaded the Fifth and lost his career for it. Unlike Rossen, Polonsky never got to direct another Hollywood film, his filmography curtailed to a slate of screenplays and the one directorial effort, Force of Evil (1948), another terrifically terse and NYC-set noir classic also starring Garfield (this time swapping the gloves and shorts of devil’s fighter for the suit and tie of devil’s advocate).

Before all that, for a brief moment in 1947, Rossen and Polonsky’s collaboration pulled no punches in its lesson on how pride comes before a fall and everything has a price. Body and Soul remains a knock-out for its noir atmosphere of moral gangrene and unbridled greed, its dynamic cinematography by the legendary James Wong Howe who filmed the boxing sequences from inside the ring on roller-skates, and its obvious influence on many a later boxing pic, not least Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull.

10. Quai des orfèvres (Henri-Georges Clouzot)

Unlike his compatriot Jean Epstein (see Le Tempestaire above), the so-called ‘French Hitchcock’ Henri-Georges Clouzot had kept working in Occupied France, a controversial move which opened him up to much criticism for continuing to make films when French studios were effectively German-owned. Come the end of the War then, he had plenty to prove and many reasons to regenerate his professional career. This eagerness led to Quai des orfèvres, his first masterpiece. Bernard Blier stars as a morose, paranoid and deeply insecure piano player — classically trained, he once harboured hopes of being a concert pianist but now instead makes a living in tawdry Parisian music halls. But that’s not even the main source of his bitterness. His younger (and prettier) wife (Suzy Delair, who passed in 2020 at the grand age of 102) is a flirt who dreams of moving up in the showbiz world and therefore has to attract attention, something which keeps her husband constantly on edge, green with jealousy, and ready to fight any man who even looks at her. When a lecherous old man who’d promised to help her career in return for unspeakable favours turns up dead, the husband is the number 1 suspect; but as always in Clouzot’s fictional world, nothing is as simple as it seems.

Clouzot’s reputation remains that of a cynical pessimist who sees the worst in people and portrays the world as a morally bleak place. Some of the seedy vision of Paris he recreates here might superficially support that: it is a teeming panorama of black market traders and dirty old men, prostitutes and nude photography models, crime reporters and petty gangsters, jealous lovers and much more. If Epstein filmed Brittany as if it held the entire cosmos in Le tempestaire, Clouzot is more interested in creating an entire universe and implanting it into his studio version of Paris. But the way he depicts this is far from cynical and pessimistic. Look at the warmth with which he shows the backstage camaraderie of the many different music hall performers, or the gay subtext of Simone Renant’s love for Suzy Delair upon which much of the plot hinges, or most of all the world-weary widower detective (whose gaze seems is the one Clouzot most relates to) so brilliantly acted out by Louis Jouvet. There is sympathy, and empathy, and love in these characters and their feelings for the world and people around them… Far from being a cold, bleak window into post-war France, Clouzot instead manages to find warmth and personality in the darkness, in the details of his many characters and scenes, and it is this which makes Quai des orfèvres a film worth watching and re-watching.

9. Motion Painting No. 1 (Oskar Fischinger)

In 1947, films were, for the most part, classically narrative in their conventions. The modernist exercises of a Bresson or a Rossellini were still a few years away. Classical Hollywood and its factory-like industry dominated notions of what a film was, and hence largely dominates this list. But, in the nooks and crannies of the 1947 film world, avant-garde experimenters were busy pushing boundaries, quietly and busily plugging away at artistic innovations that posed the questions, What is a film, What can a film be, What should a film be?

And so the same year saw Kenneth Anger (then aged 20, today still around and active at 95) make his cult early film Fireworks, a dreamlike homoerotic short which conjures up both Aleister Crowley and Jean Genet, and which presages later, even more influential, films Anger would make like Scorpio Rising (1963). Hans Richter, Dadaist painter who had fled Europe in 1940, made Dreams That Money Can Buy, a feature-length portmanteau film whose various parts are equally oneiric and surrealistic, explore identity and the Self in various intriguing ways betraying some Freudian influence, and which (I’d bet my bottom dollar) a certain David Lynch must have watched and absorbed into his subconscious. Elsewhere, but also in 1947, Beatnik-bohemian Harry Smith experimented with directly dying the celluloid frames, painstakingly creating abstract shorts which give the feeling of looking into petri dishes of exploding Venn diagrams of interconnected colourful shapes.

Amongst all this fascinating flurry of artistic effort, my personal favourite is the work of Oskar Fischinger, another emigré from Europe, initially brought to Hollywood to do animation work on Fantasia but then shunned by Walt Disney (who still used Fischinger’s work anyway). His abstract animations go one step further than Harry Smith’s: in his 1947 work Motion Painting No. 1, Fischinger not only paints shots and frames (using oil paint on plexiglass) but syncs the whole thing to music, namely Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 3. The impact of watching it feels like visualised music, long long before this effect had been cheapened by ubiquitous Windows screensavers, every changing second realising the magic of rhythmic editing, of that perfect alchemy between image and sound, between colour and tone, between gradations of shape and gradations of music. Who says film has to have a narrative? You can lose yourself in this and make your own, as can you in all Fischinger’s other abstract animations which I equally recommend (check out the earlier animated short he made with a similar ethos, the self-explanatory title An Optical Poem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Xc4g00FFLk).

8. Antoine et Antoinette (Jacques Becker)

It has become a commonplace cliché to describe Jacques Becker as an underrated director. Certainly, for a long time, he was, in comparison to other contemporary French filmmakers. But it is equally true that the process of Becker’s rediscovery by cinephiles is well under way: retrospectives at the French Cinématheque, at the British Film Institute, Blu-ray box-sets of his films. Becker is no longer a well-kept secret and we can now realise that his very strengths are part of the reason he never fully got his dues. Not an obvious auteur, Becker was a versatile director capable of the Renoir-esque (he was erstwhile AD to Renoir) and the Bresson-esque (see his final film Le Trou), as well as charming romantic comedies that feel a precursor to the Nouvelle Vague in their light, energetic naturalism. Antoine et Antoinette belongs to the latter category, and within an already overlooked filmography, it is his sprightly, pitch-perfect rom-coms which are dismissed as ‘slight’ — the great André Bazin himself called it inferior to Becker’s other films, in large part because he felt Becker did not understand the working class world in which it is set.

Looking back on it today, this feels unfair. Antoine et Antoinette takes place over one weekend and follows the trials and tribulations of the titular twosome. He is a worker in a printing factory; she operates the photo-booth in a department store. Together they make ends meet in a post-war Paris where food is still rationed, living on the top floor of a communal building, their small attic-apartment being where they day-dream about the future, a motorbike, a family, a bigger place to live in. Dreams which are fragile and precarious, but dreams which seem like they might just come true when, mid-way through the film, the narrative thrust solidifies around a winning lottery ticket which then cruelly goes missing… Everything that had been set up before that perfectly pays off in the second half.

Becker is at his best with characters, routines, and small details: the books Antoinette gets from Antoine and lends to her workmates at her store, the local bar-owner’s daughter’s wedding in preparation, the young aspiring boxer living next door with his parents, the lusty greengrocer on the other side of the street whose malignant lust toward Antoinette causes havoc, all this and more serve not just to add texture to the film but end up being crucial parts of the plot. Naturalistic and ever-charming, Antoine et Antoinette feels as if Becker was refracting the influence of René Clair (see Le million) after having binged on Hollywood screwball comedies and Italian Neo-realism: the location shooting and scenes in the Paris metro give a sociological slice-of-life feel to the film. Leave behind the idea that this is somehow ‘slight’ because it is a sprightly comedy about a young married couple, and enjoy all it has to offer.

7. Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Yasujiro Ozu)

Minor Ozu? Perhaps. But minor Ozu still ranks among the finest of films by any barometer.

After spending WW2 in colonial Singapore, doing as little as he needed to under the Japanese imperial forces’ film unit, Yasujiro Ozu returned home and continued directing films and unravelling themes right where he’d left off. There’s plenty of continuity with his pre-war films, and many of Ozu’s regular actors from the 1930s (Choko Iida, Chishu Ryu and Takeshi Sakamoto) reappearing in his post-war output including in this, his first film made after the war. Iida, who’d been the mother in The Only Son (1936), stars as a curmudgeonly widow who reluctantly takes in a young abandoned boy.

At the same time, so much had changed in the 5 years since the previous film he’d made (There Was a Father) and so Record of a Tenement Gentleman, like almost every film on this list, is addressing new post-war realities in 1947. Note the poverty of the war orphans depicted in the memorable closing shots, or the fact Iida’s character herself is a widow, or the stoically melancholy and wryly humorous attitude towards loss and regret that imbues the film’s tone and would come to shape the mood of Ozu’s later masterworks. The unsentimental central relationship between a makeshift parent and child who learn to get along almost despite each other has reflections even in later films around the world, from Cassavetes’ Gloria (1980) to Koreeda’s Shoplifters which also explores the idea of chosen family ties over biological ones — it also echoes some of the themes in Allan Dwan’s Driftwood (see no. 19 above).

But, as always with Ozu, it’s the details, the charm, the running jokes of runny noses, the way Iida responds “I bite” when her friend calls her the boy’s grandma rather than mother, the geometric compositions and visual playfulness, that make the film worth watching and re-watching with pleasure. Minor Ozu? No, simply Ozu somewhere in the middle of his career, in full flow, while also making a subtle transition. But more than anything it’s simply Ozu, and that’s a cinematic gift to treasure in any year.

6. Odd Man Out (Carol Reed)

As far as collective memory goes, Carol Reed as good as invented the British noir in 1949 when The Third Man immortalised post-war Vienna — canted angles and overblown shadows in the dark alleyways of a big city, a post-war mood of something being deeply wrong, existential overtones… But already it was all here, two years earlier, in Odd Man Out, the film that kicked off his most fertile period (in the space of two years, he made his three masterpieces: Odd Man Out (1947), The Fallen Idol (1948) and The Third Man (1949)). What Vienna was for The Third Man, Belfast is to this. The city is never named, nor is the nefarious ‘Organisation’ for whom James Mason’s Johnny works for ever explicitly referred to as the IRA. All this we infer. Make no mistake, Odd Man Out is a far more abstract, philosophical, even quasi-spiritual film.

The ‘odd man out’ of the title, and the character whose metaphorical road to Calvary the film charts, is Johnny (James Mason, appearing again on this list after The Upturned Glass above), a local IRA leader recently out of jail, where in his time alone with his thoughts he acquired serious doubts about violence being the correct means to achieve their ends — hence redemption is already part of his arc from the beginning. Stubbornly, Johnny insists on leading the group on a heist for funds (he and his associates need money for their more political aspirations) and when he botches things up, he is left injured, on the run, and suffering from a vertiginous mental trauma. During the 12-hour period which the film narrates, Mason has the constant look of a doomed, cornered animal, like so many noir protagonists, trapped under the weight of his life’s burden and contested between all the many interested parties he meets or bumps into along his nocturnal odyssey through one fateful wintry Belfast night.

Reed’s film is a perfect example of how, by 1947, the movies were a medium mature beyond mere entertainment or star-making, a medium now fully able to flex its existential muscles. The decision to leave nothing specifically revealed, to make everything feel more universal and abstract means this is not a film about one political organisation, nor a sectarian struggle between Protestants and Catholics, and not a film about the contemporary values and opinions on those issues. Instead, Odd Man Out stands the test of time for it is a film about one man and the tug-of-war for his soul, between various individuals and groups all wanting a piece of him for different reasons: the woman who loves him with a quiet but intense passion, the dutiful police chief determined to lead his men to Johnny’s capture, the avuncular old priest wishing to offer final redemption for the man he knew as a boy, the drunken painter longing to immortalise Johnny’s death’s-eye stare, and many others plotting after the reward money on his head.

The Third Man gets the plaudits and seems to be the better-remembered of Reed’s films, but yet Odd Man Out has a deep legacy of its own. Watching it again while making this list, I was struck by similarities with a much later classic of British cinema, also the nocturnal odyssey of an ironically Christ-like character named Johnny, Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993), both films knowingly striving for mythic overtones. I would be quite surprised if it was not somewhere in Leigh’s conscious when he was planning Naked‘s structure. But like Leigh’s film, it is also much more than some symbolic existential allegory, it is brimming with the panorama of life, with the bustle of a living city, with children playing, stray dogs chasing, young couples searching for a private tryst, opinionated community folk, and a deep sense of poetic realism. It also has a mix of moods and registers (which the film’s critics claim make it tonally inconsistent, but in many ways make it even more enjoyable to watch), such as the over-eager performance of Robert Newton at times hamming it up as the painter who takes in Johnny, or the expressionistic flourishes like Johnny being lost in thought visually represented by the bubbles of his beer coming alive to talk to him as he stares at it… This is much much more than your everyday noir.

5. Daisy Kenyon (Otto Preminger)

5. Daisy Kenyon (Otto Preminger)

When Otto Preminger signed off on Daisy Kenyon, the second film he made in 1947 and on paper the lesser sibling to the more high-profile, Oscar-nominated, literary adaptation Forever Amber, he couldn’t have known that he’d just directed a film that would retain a cult following 75 year later. In fact, interviewed years after, he admitted not remembering much at all about the making of this film.

Yet, if you watch an array of 1947 Hollywood films, it is Daisy Kenyon that immediately jumps out at you as being a unique film. Therein lies the collaborative magic of studio filmmaking at its finest; even without the realisation they were working on a classic, and simply going about their craft the best they could, every department of 20th Century Fox was showcased at the top of its game on Daisy Kenyon, and magic formed through the synthesis. Now rightly reappraised as one of the finest, most nuanced Hollywood movies about relationships from any era, it has the potential to make even the seasoned cinephile rethink their expectations of 1940s Hollywood cinema.

The plot premise is simple enough and does not begin to tell the full story: a love triangle forms between an independent NYC artist (Joan Crawford as the titular Daisy) and two WW2 vets, one married (Dana Andrews) and one a PTSD-suffering widower (Henry Fonda). The film’s hugely impressive achievements lie in illuminating the depth of every nook and cranny of this triangular relationship, in depicting fully-fleshed out and believably flawed characters in a mature and sophisticated way that never condescends. These are characters who are not onscreen to be judged or to elicit simple emotional reactions, nor is their dialogue lifted from a screenwriter’s manual. Everything feels fresh and lived-in; just compare the controlled anguish of Crawford here with her more theatrical performance in the paranoid Possessed (also 1947) or the consummate skill with which Henry Fonda connotes the passive aggression of his benign-but-calculating widower. The candour feels so fresh, the un-showy performances of the three stars so natural, and the unjudgmental ambiguity with which the issues are dealt with feels so modern and so… well, adult for Hollywood in any era let alone 1947.

And that’s without even getting to all the issues handled in the film’s background: there’s adultery, divorce, child abuse, and even reference to the Japanese-American internment camps 43 years before Hollywood would make a movie about it (Alan Parker’s Come See the Paradise in 1990). These issues add surface depth, providing even more nuance, but none overwhelm the picture. To the very end, the emphasis remains on the love triangle and its dynamics, fluctuating our sympathies between Crawford, Andrews and Fonda. If even Preminger couldn’t remember it, it’s enough to make us wonder how many more forgotten gems of the classical Hollywood era remain out there waiting to be re-discovered.

4. It Always Rains on Sunday (Robert Hamer)

Room for one more British film noir on this list, and the best of the lot to boot. You wouldn’t expect noir from Ealing Studios, still fondly remembered for their classic comedies, but in fact Robert Hamer’s It Always Rains on Sunday was Ealing’s biggest box-office draw of 1947. Hamer, who would direct Kind Hearts and Coronets two years later, was already establishing himself in these post-war years as a great director of the undercurrents of British society, capturing the class tensions, restrictive conformity and social repression of Britain with great wit and cynicism.

The narrative plays like a gender reversal of the classic noir formula: the protagonist attempting to live out her life and forget the past is a woman (played by the wonderful Googie Withers), settled down in a dull marriage with a nice-but-older husband and three stepchildren. Of course, the past comes back to bite her, in the form of an ‘homme fatale,’ her ex-lover escaped from prison (fugitives are a bit of a trend in post-war British noirs…) and who hides out at her house threatening to ruin the steady boring life she has created for herself. The whole thing takes place over one Sunday (hence the title, and yes there is rain) which adds tension to the proceedings. Will Googie Withers throw away everything and run off with this old flame? Will she manage to extricate herself from the claws of this ghost of the past and continue with her unexciting life? Is that even still possible or desirable now? The noir aura of doomed fate weighs more heavily than it has any right to in the film’s lower-middle-class East London milieu.

Realising and maintaining that noir tone without ever compromising the British-ness: therein lies this film’s towering achievement. Like Cavalcanti’s They Made Me a Fugitive (see above), this is a studio film rooted in a desire for greater authenticity and detail, visible all over this one grim Sunday in Blitz-scarred East London: the grocers and the small streets, the weekly boxing on a Sunday afternoon, the beer and darts down the pub, the slow boredom of a Sunday, the colourful array of flawed characters ranging from a journalist hungry for a scoop to an unfaithful sax player, via small-time criminals. Men in general in the film are shown in a critical light, highlighting the film’s sharp cynicism. Either they’re harmlessly dull at best (much like the husband in David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945)), or willing to sell out women at worst. The women suffer at their hands simply because they want something more exciting than a life of drudgery staying home. Is there nothing else for a woman in between the threat represented by the convict on the run, and the total suppression of passion in a life of endless Sundays? The film asks and explores whilst always remaining entertaining, tense, original, locally authentic, and tonally consistent. A masterwork of British cinema.

3. Black Narcissus (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger)

Yet another British film on the list, though this time not a noir nor a film interested in dealing with the after-effects of WW2, but instead a febrile, operatic Technicolor psycho-melodrama of nuns on the precipice between emotional repression and hysteria in a Himalayan convent. Simply put, there is nothing else like Black Narcissus in 1947: just compare it with other British Technicolor films of the same year, such as the staid and lifeless Oscar Wilde adaptation An Ideal Husband. Black Narcissus on the other hand positively simmers at every instant with pent-up passions, exoticism, eroticism, and the jaw-dropping spectacle of the most striking matte paintings ever created in film history (of course, the film was shot at Pinewood Studios, London, rather than on location).

By being able to carefully control the artificial reality of their film, the magic of Powell & Pressburger (and their cinematographer Jack Cardiff) creates an unforgettable aesthetic experience, but also (in the same year that India achieved independence) it rescues the film from being no more than a colonial gaze onto India. This is not a realistic view in any way and we are constantly reminded of that. This is an India of the imagination and the film is every bit as much about the effect of the exoticised and romanticised notions of the distant, unknown lands on the white colonial psyche, as it is about anything else.

Every technical element in the film serves to reinforce the mental impact caused by the landscape, the colour, the scents, this foreign alien world the nuns are naively entering. Never has the cinematic medium so beautifully been used to chart the psychic entry of characters into an exotic which is never fully accessible to them, the exotic of this ‘foreign land’ and its intangible power, while also in parallel the exotic of that other unspoken power: physical love and longing, every bit as powerful and unattainable to these nuns forced to forego the material for the spiritual. As we all know, it crescendos into a heady, inevitable climax, but the force-field of the film has lingering influences in the decades ever since, even in unexpected places. Scorsese is an uber-fan, and the way Black Narcissus unashamedly uses colour symbolism to overpower the image and reflect the characters’ uncontrolled emotions (blue springs back Deborah Kerr’s character to her idyllic past, or red flashes restricted lust across David Farrar) has been directly picked up by Marty in his own films (just think of the way the screen bleeds into yellows and reds in Scorsese’s own melodrama The Age of Innocence). And even John Carpenter had the iconic hair and make-up of the bedevilled Sister Ruth atop the bell-tower in mind when making Christine, a very different film also about a strange kind of maddening mental obsession.

2. Brute Force (Jules Dassin)

Burt Lancaster, fresh from his 1946 breakthrough in The Killers (directed by Robert Siodmak, produced by Mark Hellinger) confirmed his ascension to stardom in what is probably Hollywood’s greatest ever prison movie Brute Force — directed by Jules Dassin and also produced at Universal Studios by the great Mark Hellinger who sadly died in 1947, robbing us of many great movies that might have been.

The Hellinger connection forces comparison between the two films and there are obvious similarities: they share a lead star (Lancaster), a composer (Miklos Rozsa) and a few supporting actors (Sam Levene, etc). They also share the use of flashbacks, although in Brute Force it is a less elaborate and more sparing use: short flashbacks are employed to show us the backstories of how the men got into jail. Both films are peppered with memorable secondary characters who add real texture to the narrative, for example in Brute Force the great Trinidadian actor-singer Sir Lancelot as an eccentric cellmate whose intermittent songs add commentary to the plot’s events.

But the differences are enlightening: The Killers is certainly more existential, while Brute Force is more animalistic, about the body rather than the soul: what happens when men like those in The Killers have their bodies locked up in jail and their spirits caged? As for Lancaster, his roles are poles apart: in The Killers he is a fatally doomed patsy who suicidally gives up when faced with Death; in Brute Force, as the indomitable jailbird Joe Collins, whose rebellious spirit reminds me of a prison version of Randle P. McMurphy, Lancaster heads an escape plan which, though it may be equally suicidal, means the men will certainly not go down without a fight.

And the fact the film’s sympathy lies on the side of the prisoners shows just what a radical movie this was by 1947 standards. The doomed-but-likable heroes are the jailbirds trying to escape a brutal, authoritarian and thoroughly de-humanising prison system. We feel for them, come to like them, see them almost as if they were POWs in a war camp rather than the convicted criminals we know them to be (and the film does not romanticise this: they are criminals, but they are also human beings too).

The sadistic and manipulative prison warden Captain Mundsey (played by Hume Cronyn as an effete, social-Darwinism spouting torturer who could easily be a Gestapo officer), who craves the fear of his prisoners, is Brute Force‘s equivalent of Nurse Ratched, to continue the One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest analogy. Everything is turned on its head in Brute Force: it is the system that is to blame, not individual criminals, and what’s more than that the film’s characterisation of Mundsey (who even listens to Wagner in his office) hints that fascists may still be around closer to home and even with WW2 won.

Those who want to do good within the system, meanwhile, are shown to be impotent. Dr Walters (Art Smith), serves as the archetype of the ‘witness corroded by evil he sees but is powerless to change’ character, similar to John Hurt in Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, Walter Brennan in John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock, or even Morgan Freeman in David Fincher’s Se7en. He is a world-weary, philosophical type, with a close bond to the prisoners. He often drinks, of course to forget the things the abuses and injustices he sees which disgust him, in a job he cannot bring himself to quit. But is there any redemption for him by the end?

It took all of Hellinger’s own untameable rebellious spirit (we can see some of Joe Collins in him) to win his dogged battle to get the film past the Hayes code censorship without compromising his vision of it. And it cost Jules Dassin his Hollywood career as the film’s politics (painting the USA’s prison system as fascistic and the prisoners as exploited proletariat) obviously fell prey of the HUAC McCarthy witch-hunts, forcing him into a European exile. But… but Brute Force is also much more than a radical sociological critique of the prison system and of authority within society. It also stands out in 1947 as an absolutely brutal punch of a movie, as brutal as its title or as the microcosm of society it depicts. That it ever got made in Hollywood in any year, let alone 1947, is remarkable.

1. Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur)

No genre better captured the post-WW2 zeitgeist of fatalistic determinism than film noir. Temporarily, the mood of Hollywood movies became bleak and tragically romantic, its protagonists were cornered animals acting as target practice for time’s arrow, unable to release themselves from the stranglehold of the past and viewing the future with nothing but uncertain trepidation. And no film read the runes better than Out of the Past.

On one level, it is the quintessential film noir: Robert Mitchum is at his most placidly hard-boiled as the doomed hero; Nicholas Musuraca’s cinematography transitions from expressionist shadows highlighting the precarity of Mitchum’s fate to more even balanced lighting to represent the small-town America Mitchum tries but fails to assimilate into; Jane Greer as the femme fatale is part spider-woman capturing Mitchum as her prey and part tough dame just trying to survive in a man’s world; and the motif of cars, roads and petrol stations seen as symbols of fate in so many other contemporary noirs (The Killers, Detour, They Live By Night, etc) plays a major role.

Like Robert Siodmak’s The Killers, Jacques Tourneur’s noir classic begins in a sleepy Californian any-town, short-lived shelter to a man trying to make a new life for himself by working in a petrol station, as if trying to stem Fate’s flow in the form of the cars moving in and out of town. Of course, just as it was for Burt Lancaster in The Killers, these are men who constantly have one eye on the rear-view mirror and the past ends up driving right back into their lap. We then see the past Mitchum was trying to erase in a Mexico-set flashback, framing a fateful meeting with Jane Greer’s femme fatale in Acapulco, where her entrance remains iconic (“Now I knew why I was being paid 40k to track her down” notes Mitchum’s laconic voiceover).

Yet, on closer inspection, Out of the Past is a one-of-a-kind movie belying all the conventions of noir, unforgettable, undefinable and poetic. What other noir, so typically an urban genre of the mean city streets, lingers on the soft haze of Acapulco beaches and the shimmering surface of Lake Tahoe? What other classic noir has a moment as dreamy as that when, after Mitchum and Greer seal their tryst in her bungalow and dare to think of running away together, the ominous wind slams the door open, the music swells, and the camera with a mind of its own takes us to the rainy tropics outside the house? How many other noirs have a narrative structure that mirrors their theme so perfectly, setting up the past with a flashback section that is then repeated in the present, only to show the inescapability of the past’s legacy? To underline how the past can only repeat itself, the narrative structure of the film shows us the past literally happening again before our eyes. Mitchum makes the same mistakes from Mexico in the second act in San Francisco, where he over-estimates his ability to out-manoeuvre his destiny (or, depending on your interpretation of what is a tortuous and ambiguous noir narrative, perhaps masochistically sacrifices himself so that the ‘good’ woman who loves him back in that quiet California town can get on with her life without his tainting presence).

And that is to say nothing of Kirk Douglas’ scene-stealingly suave villain, ever believable as the gambling mobster who rides the fine line between organised crime and respectable business so sinuously. Nor of the art direction where every small prop is a potential extra clue: the fish-nets on the beach in Acapulco casting a shadowy trap over Mitchum’s silhouette as he makes the fatal wrong turn of falling in love with Greer; the paintings of women on the walls of Douglas’ villa, casting him as a man who loves to frame women, possess and objectify them as he does his racehorses. Nor of the memorable costume design which makes Greer’s character don nun-like dresses that make her look like a murderous angel of death, a black widow come to mete out Fate’s judgment. No doubting it, Out of the Past is a film with its own memorable logic.

Either way you look at it, quintessential or uncharacteristic, this register of film noir dives into a most un-American of themes: the impossibility of second chances. There is no starting again, no chance of a new life or new identity, no escaping the past and indeed the vagaries of fate lead it right back to you with a bite every time. A lesson that would mark an un-escapable legacy on much Hollywood cinema to come; Rock Hudson would learn it the hard way in John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, as would Viggo Mortensen in David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence.

See also: Pursued (Raoul Walsh) — for a double-bill of Robert Mitchum at his languid, brooding best, follow up Out of the Past with this western noir, one of the first Freud-on-horseback movies to introduce psychological themes to the cowboy genre, beautifully shot by James Wong Howe, and from a screenplay by Niven Busch that has all the ingredients of a classical Greek tragedy.

One thought on “My Best Films of 1947”