![]() Manila in the Claws of Light (1975)

Manila in the Claws of Light (1975)

What stories are buried underneath the glittering facades of our ever-changing, crane-filled cities? What trajectories and narratives do those who toil in building this urban flux follow? In today’s era of global neoliberalism, from New York to Singapore, London to Dubai, glass towers reach the sky like impossible-to-avoid monuments to wealth, while the lives of those who build them, clean them, and sometimes die whilst constructing them, remain offscreen. Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975) is a direct challenge to this cloak, specifically in Marcos-era Philippines but remains globally relevant and prophetic 50 years on. Made during a time when Ferdinand Marcos was desperately trying to rebrand the Philippines as a modernising, internationally respectable state, Brocka’s film exposed the ugly scaffolding behind the illusion: poverty, exploitation, and human cost. Shot with gritty realism, simmering rage, and Brocka’s trademark breakneck energy (in the ’70s he often made four or five films per year, though few as heartfelt as this one), it remains one of cinema’s clearest visualisations of how cities consume the very people they depend on, leaving behind shattered bodies, broken dreams, and unanswered screams.

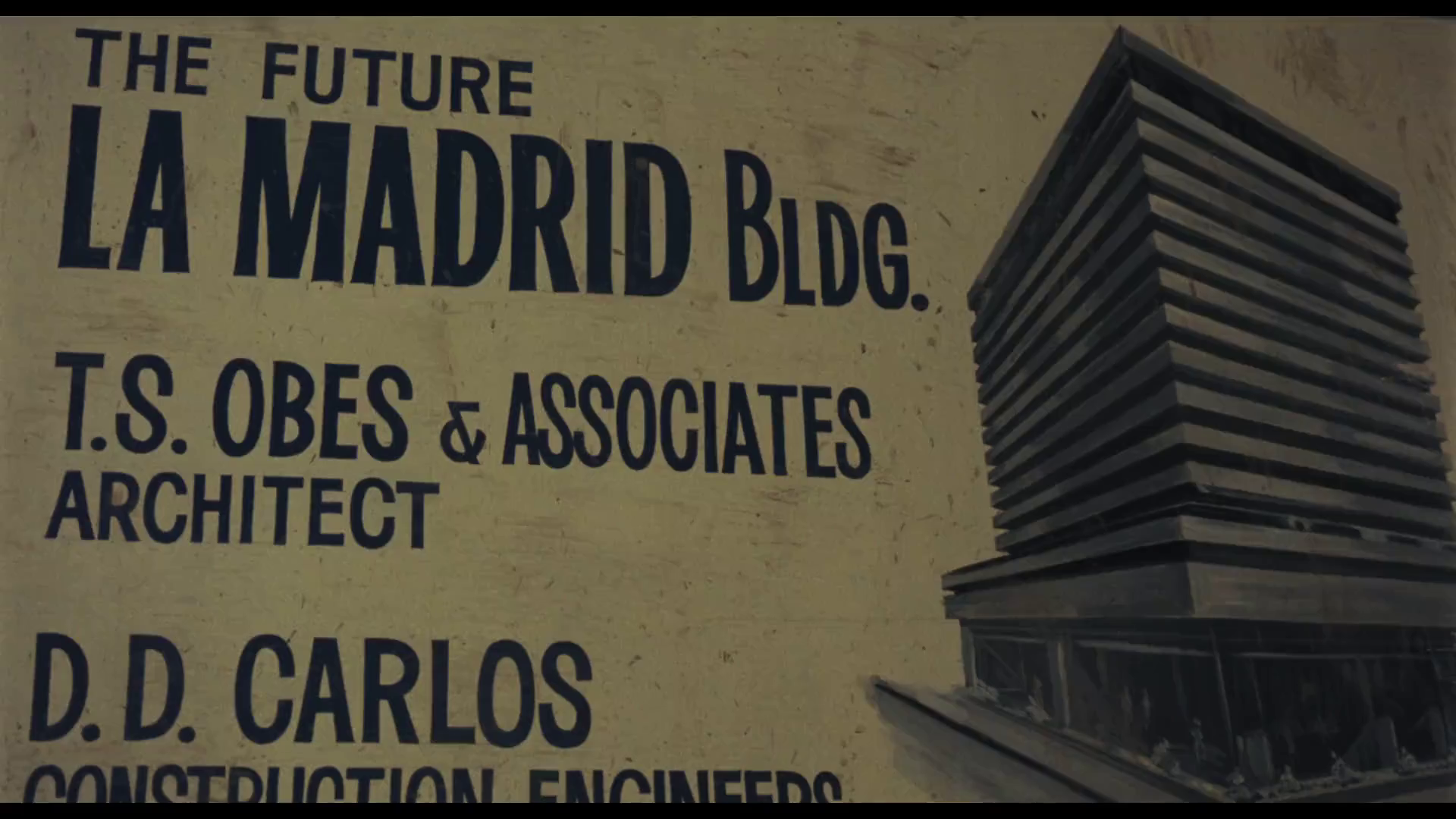

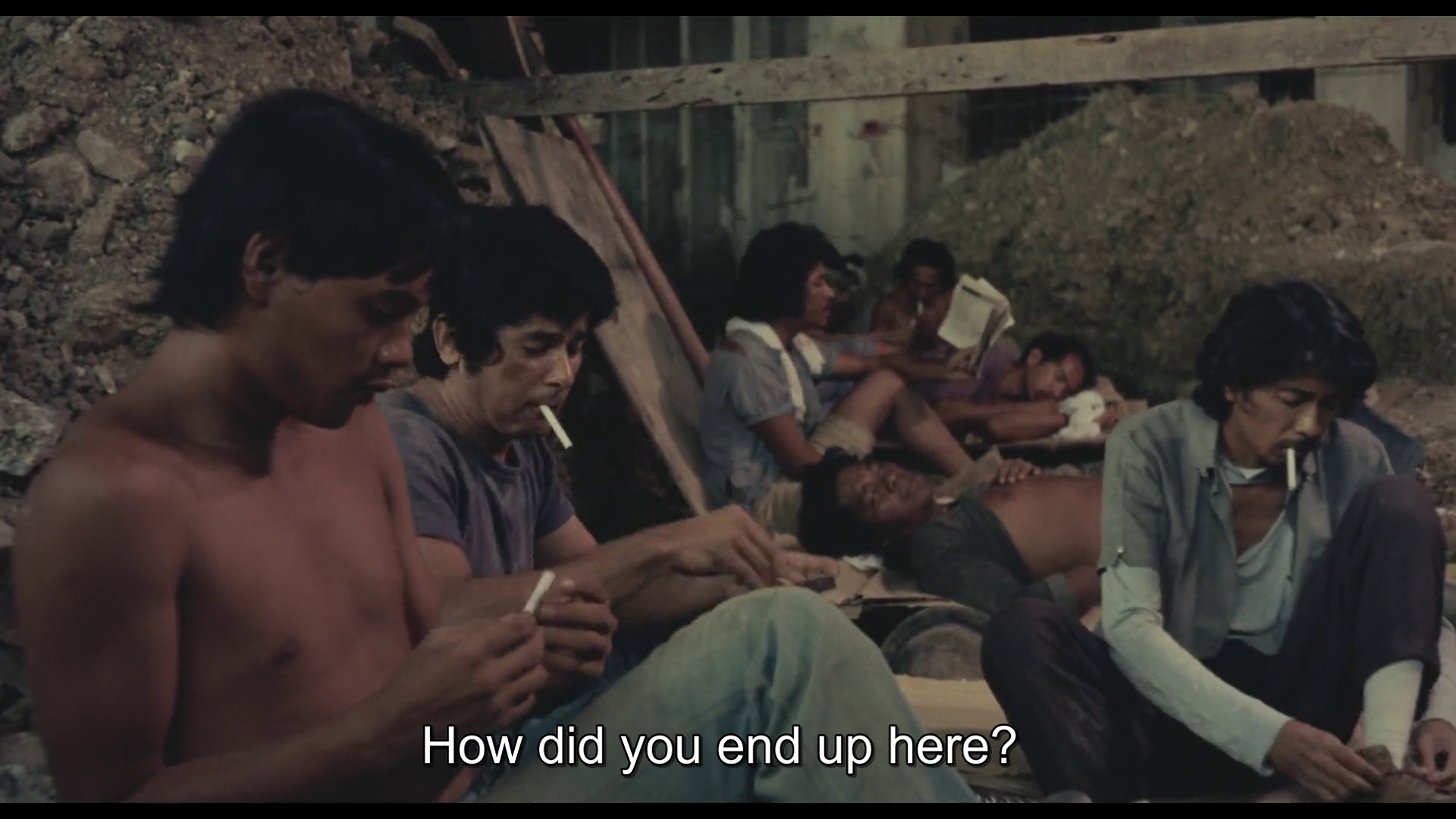

At its core, Manila in the Claws of Light is an archetypal narrative of rural boy moving to the city, as well as a quest narrative, but one where the hero’s transformation is a descent into corruption and corrosion. Julio Madiaga (played with cherubic innocence by then-newcomer Bembol Roco) is a young fisherman from the rural island province of Marinduque, who arrives in the capital searching for Ligaya Paraiso (Filipina screen legend Hilda Coronel although she gets little screen-time here), his vanished girlfriend lured to Manila by promises of work and schooling. Her name (Ligaya means “joy” and Paraiso means “paradise”) quickly becomes painfully ironic, a memory that haunts Julio as he’s absorbed into the city’s underworld. He finds work on a high-rise construction site (Image 1), faints from hunger, sleeps on-site, and is later drawn into sex work when left jobless. The city doesn’t simply challenge him, it eats away at his soul, from one job exploiting his body’s labour to another, gradually stripping away his innocence and humanity. At one point, unleashing his pent-up frustration by brutally beating a pickpocket in broad daylight, he looks at his own hands in sudden realisation at what urban life has turned him into (Image 2). His search for Ligaya becomes a search for something inside himself slipping away, the ‘paradise lost’ visualised in the innocent rural flashbacks we see of Ligaya and himself as childhood sweethearts back on their island (Image 3), or perhaps simply the capacity to survive without becoming animal.

Much of the film’s power lies in how Brocka and cinematographer-producer Mike de Leon (who one year later would make his own directorial debut with Itim) map Manila not just as a physical environment but as a psychological maze. In the first section, unfinished constructions loom like skeletal symbols of modernisation, for a future that not all will have the privilege to share in (4 &5). On the outskirts of the city, unhygienic slums stack families into tiny shacks of wood and corrugated iron (6), exactly the kind of image of Manila the Marcoses dreaded foreigners seeing and wanted to suppress. In Binondo, Manila’s colonial-era Chinatown adorned with 19th-century stone houses from a time when Chinese migrants prospered commercially, Julio obsessively stakes out at a street corner (7) where he once saw a potential lead to Ligaya’s whereabouts. At other times he traverses busy markets, decaying cinemas, and red-light districts that glow with predatory neon, all the more emphasised by the surrounding pitch blacks of de Leon’s cinematography.

Visual contrast is starkly created between the artificial lights of Manila and the warm, sunlit rural flashbacks which Julio keeps remembering, giving us a glimpse of the ‘paradise lost’ he carries in his mind. When he finally finds Ligaya again, surreptitiously in a church, some critics claim to find it too melodramatic, but it could just as easily be inside Julio’s head, a mental construct like his nostalgic visions of the past: Ligaya returns fleetingly for one night only to vanish once again. In the end, it is the city which dictates its characters’ fates, becoming a shape-shifting trap: characters move to it and within it, but like moths drawn to the light of a flame they cannot escape. The film ends in an alley, a dead-end as dead as Julio’s hopes where he, now having committed murder, is cornered with nowhere to go. It is not just a tragic conclusion but a spatial argument: rural migrants enter Manila, but they do not leave. They are absorbed, erased, and forgotten.

The powerful panorama of Brocka’s indictment extends beyond Julio. The film becomes a mosaic of invisible lives: Benny, who dreams of being a singer, dies in a construction accident, his torn songbook left amid the rubble like the wreckage of his hopes (8). We see also — and this makes Brocka’s film even richer — the camaraderie, that other side to the urban underworld, and the friendship and warmth which Julio receives from some and which he returns (9). We see the world of brothels, prostitution and gigolos. We even see a glimpse of a Filipino Communist Party demonstration (in which the march is led by none other than fellow Filipino filmmaker Mario O’Hara in a brief cameo), a sign that the film is probably set just before martial law when Marcos’s regime would have such marches totally illegal.

What we do not see is also important. Atong, Julio’s fellow worker, is killed after daring to confront a corrupt foreman; his sister, caring for their paralysed father in a shantytown shack, has her precarious home burned down by police thugs and is coerced into sex work — all events which happen offscreen. Ligaya herself, coerced into an abusive relationship with a Chinese-Filipino man, is barely glimpsed before we learn of her denouement, also offscreen. These absences matter. Brocka refuses to exploit their suffering for sentiment. Instead, their invisibility mirrors the ways systems of power insidiously render such lives disposable under the radar.

One thought on “Manila in the Claws of Light (Lino Brocka, 1975)”