Introduction

(Note: this article uses the naming convention of placing Japanese surnames first, before given names.)

If I was ever forced to choose, I would have to pick 1960s Japanese cinema as the greatest pound-for-pound decade of any national cinema. If it seems a surprising choice, just bear in mind the abundance of riches all co-inciding in this same decade. The old masters who’d started in the silent era (Ozu, Naruse) were still making masterpieces. The generation of directors who broke through post-war (Kurosawa, Ichikawa, Kobayashi, Shindo) are still in their prime and making some of their best films. And then, there’s the incredible innovation and energy of the Japanese New Wave crashing into the picture (Oshima, Imamura, Shinoda, etc), not to mention the jazzy psychedelic yakuza pulp films of Suzuki Seijun or lots of other great genre film-making. What an era…

And in the midst of all these came some genuine “UFOs”, unclassifiable films that don’t quite fit in any category but only serve to make 1960s Japan an even more fascinating cinematic terrain to explore. One example is provided by the alliance between director Teshigahara Hiroshi, writer Abe Kobo and composer Takemitsu Toru who together made four quite remarkable films: Pitfall (1962); Woman in the Dunes (aka Woman of the Dunes, 1964); The Face of Another (1966); The Man Without a Map (1968). These films often tend to be grouped in with the Japanese New Wave, but to my eyes they stand apart. These are idiosyncratic and unique films which were the fruits of a collaboration unlike anything else happening at the time. Critics have compared their style with the modernist European art-house cinema of the same era, as typified by auteurs like Antonioni, Bergman or Resnais. Whatever small accuracy there is to that comparison, it short-changes the uniqueness and specificity of what was a distinctive partnership, and the particular climate in 60s Japan in which it formed.

In this essay my aim is therefore to focus on the specifics around the films Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu made together, and their context. The most pressing contextual question is: how did these three men who came from backgrounds that initially had nothing to do with cinema (Teshigahara was a painter and trained in fine arts; Abe was a playwright and author; Takemitsu was an avant-garde composer and musical theorist), how did these three men come to make four breakthrough films in 1960s Japan? Especially considering that in the 50s, the Japanese film industry was one of the most rigidly hierarchised studio systems in the world, in which anyone wanting to be in the director’s seat had to do a lengthy apprenticeship (often as long as five years or more working as assistant-director) and independent cinema made outside the studios was non-existent. So what changed in the 60s to open up filmmaking in ways it had previously been closed? The seismic shifts which occurred in this period are a key part of the story I hope to narrate. But first things first, let us start at the beginning and look at the Japan these three future artists were born into and grew up in.

Teshigahara, Abe, Takemitsu and post-war Japan

Teshigahara Hiroshi was born in Tokyo in 1927, the son of Teshigahara Sofu, a renowned master of ikebana (the Japanese art of flower arrangement). Sofu was a progressive, eclectic artist who had invented a new form of ikebana, a rare feat in the conservative world of traditional Japanese arts. Hiroshi thus grew up within an artistic legacy, and initially chose to study painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Abe Kobo, on the other hand, came from a less privileged background. Born also in Tokyo, in 1924, his family thereafter moved to Manchuria, then a Japanese colony, where he spent most of his early life. It has often been suggested that seeing the brutal injustices of Japanese colonialism first-hand, as well as the desert-like landscapes of Manchuria, were formative experiences which would later be projected onto his art. In his own words:

“I remained in Manchuria for a year and a half after the war and witnessed the complete destruction of social order there. That made me lose all trust in anything stable.”

Abe also spoke of the culture shock in returning to Japan after the war, a country supposed to be his homeland but which he hardly knew at all, giving him an outsider’s perspective:

“My place of birth, the place where I grew up, and my place of family origin are all different… Essentially, I am a man without a hometown. The sort of aversion I have for hometowns… could be due to this background.”

Here the themes of alienation and identity, later to become trademarks of his work, are already emerging. This experience also foretells his strong anti-nationalistic feeling — Abe was an internationalist, with little regard for borders, who believed in doing away with nationalities.

Takemitsu Toru, born in Tokyo in 1930, grew up a sickly child, homebound and spending most of his free time reading or listening to all sorts of music on US Forces radio stations. Though he was expected to follow in the footsteps of his businessman father, he instead pursued the passion aroused in him by those early broadcasts of Duke Ellington and other jazz, and became self-taught in musical composition. Such an outpouring of American and Western influences and their enthusiastic reception post-war might have been expected, since they had been banned during the war and were now discovered for the first time with a sense of curiosity by many young Japanese. Not only that, but naturally those who were now reaching adulthood in the post-war era were eager to disown the past. The horrors which had resulted under the extreme militarism of Emperor Hirohito were enough to make Takemitsu’s generation ashamed of their nation. As Takemitsu put it: “Because of World War II, the dislike of things Japanese continued for some time and was not easily wiped out. Indeed, I started as a composer by denying any ‘Japaneseness’“.

So the opportunity to transform and re-define the country they lived in became an essential preoccupation for the post-war renaissance of artists, writers and thinkers in Japan. In trying to forge a new national identity, several tensions had to be negotiated: tradition vs. modernity, Japanese vs. Western, society vs. individualism, leading to various cultural ideas and theories. Concurrently with those who wanted to look to Western influences, many also wanted to look back towards the ancient Japanese traditions of a blameless pre-war culture, in particular Zen buddhism, and to find a way to apply them to new art and ideas. A large number of artistic societies were formed among like-minded intellectuals and artists from diverse backgrounds, all sharing a desire to blur the boundaries between different art-forms by working together. Experiments and radical innovations were jointly taking place in fields like literature, painting, music, dance, photography, sculpture, and calligraphy. It was in this rich atmosphere of avant-garde cross-pollination that Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu would find creative kindred spirits in each other.

When Teshigahara studied at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, one of his teachers was the abstract painter/sculptor Okamoto Taro, whom he credited as one of his primary influences. Okamoto was an energetic personality who exhorted his students to do nothing less than radically reconstruct the Japanese art world. The writer/essayist Hanada Kiyoteru and the poet/painter Takiguchi Shuzo were two other significant figures and opinion-makers inspirational to the circles which Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu frequented. Despite the three aspiring artists being influenced by various Western artists who had a deep impact on them — for example Gaudí, Picasso, Buñuel or Cocteau for Teshigahara; John Cage and Duke Ellington for Takemitsu; or Kafka, Sartre and Camus in Abe’s case — all of these were necessarily refracted through their own sense of coming to terms with Japanese identity at that time, and through the influence of avant-gardist mentors like Okamoto, Hanada and Takiguchi.

In 1948, Okamoto and Hanada founded the ‘Night Society’, a group devoted to producing truly collaborative art by crossing the barriers between genres, which Abe became a member of. However, it was not altogether successful in its goals and fragmented into separate groups; among these was the ‘Century Society’, launched by Abe himself with other members of the Night Society. The Century Society, though founded by writers, opened its doors to painters and visual artists, and Teshigahara joined. It was there that he met Abe for the first time in 1949, and the two instantly hit it off. Teshigahara would later recall his first impression of Abe as “a man interested in all the arts and seeking a way to bring them together“. Takemitsu likewise, was at that time an active member of a similar avant-garde group, known as the ‘Experimental Workshop’, which was channelling innovations in music, dance and multi-media performances. He navigated amongst the same artistic circles as Abe and Teshigahara, and in the 1950s all three would establish their own careers.

Teshigahara, initially a painter of Picasso-esque tableaus, was drawn towards the medium of film, perhaps because it had been the one art-form his father hadn’t left his own mark on. Although still lacking in technical know-how, Teshigahara got his lucky break as director of a documentary short when the original director pulled out. The subject was the Edo period wood-cut artist Hokusai (he of the iconic Great Wave woodprint), a project thus fitting with the trend of exploring traditional Japanese artistic influences, which Teshigahara could fund himself thanks to his father’s resources. While working on Hokusai, Teshigahara befriended many experienced directors, including Kamei Fumio, a left-wing social-realist documentarian, under whom he would learn the fundamentals of filmmaking as assistant-director on three films (one about the protests against US bases in Japan and two others about the effects of the nuclear bombs). However Teshigahara came to find Kamei too didactical, even preachy, compromising artistic integrity for the sake of having a clear message to get across. As could be expected from his influences, Teshigahara wanted a more balanced marriage between artistic and political interests, and sought his own path.

In 1959 he spent 4 days in New York making Jose Torres, a documentary about a Puerto Rican boxer for which Takemitsu, already an established writer of scores, was brought in to compose the music. Thus began another friendship in this triangular artistic relationship, and Teshigahara, glad to have found a composer with a talent for registering a sense of rhythm matching his images, would thereafter work with Takemitsu regularly. Abe, too, had worked with Takemitsu separately on some radio plays, allowing him to notice the composer’s knack for underpinning the tone of verbal texts with soundscapes.

At this stage Abe had made a name for himself in his writing career, having written several collections of short stories and poems, winning literary awards, and branching out to screenwriting – he wrote the script for Kobayashi’s The Thick-Walled Room (1956), one of the first films to deal with the taboo topic of Japanese war crimes. The times were also rife with political dissent, as American troops had continued to use military bases in Japan during the Korean War, causing an outpour of protests. Abe was arguably the most political of the three, and like the rest of his artistic and intellectual peers, was left-leaning in his ideology, being a member of the Japanese Communist Party until 1962, at which point he left over the party’s conservative stance towards free expression. Teshigahara, equally affected by the political atmosphere, reflected on these times: “Japanese politics was out-and-out pro-United States. None of the Japanese politicians were independent… Japanese-American relationships had started in a totally colonialistic way, and we couldn’t help being critical.”

This sense of anger at the establishment galvanised Teshigahara and Abe (whose early literary work was already heavy with allegorical allusions) into attempting to unify the arts through simultaneously political and artistic motives. Towards this goal, Teshigahara himself initiated two ventures to further diversify the growing artistic culture. When Hiroshi was handed control of Sogetsu Hall by his father in 1959, he turned it into Sogetsu Art Centre, which became a hub for all kinds of artistic activity, including Takemitsu’s concerts and experimental theatre by young innovative directors such as Terayama Shuji. Secondly, and specifically centred around his cinematic interests, Teshigahara also set up the film club ‘Cinema ’57’, screening many European and American films unavailable elsewhere in Japan. As gathering place for cinephiles and aspiring directors, it led to the collaborative project Tokyo ’58, a short documentary which Teshigahara contributed to alongside others, including another director who’d leave his mark on 60s Japanese cinema, Hani Susumu.

But by 1960 Teshigahara had not yet directed a full feature and his breakthrough in cinema was still to come. After the 1950s, the buzzword in the Japanese arts scene was now collaboration between artists, and Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu were about to put these ideas into practice in what they saw as the ideal medium for collaborative potential: cinema.

The rise of independent cinema in Japan

It goes without saying that the conservative Japanese film industry was light years away from the vanguard intellectual circles and artistic collaborations described above. So how did the film world open its doors to three members of that avant-garde art world? The series of events which laid the groundwork for independent full feature films (as opposed to the shorts which Teshigahara made in the 50s), must first be traced back to the era when the studio system was at its strongest.

Japan’s major film studios (Toho, Shintoho, Shochiku, Daiei, Nikkatsu and Toei) monopolised the industry since the 1910s, despite several attempts by filmmakers to break free. First in the 20s, directors left studios in search of greater creative freedom, for example Kinugasa Teinosuke whose avant-garde masterpiece A Page of Madness (1926) was made independently. Then in the late 40s, when independent production companies were set up by leftist directors, such as Shindo Kaneto. But overall these efforts had limited success; the studios continued to flourish, enjoying their ‘golden age’ in the 50s — with the trio of Ozu, Kurosawa and Mizoguchi all in their prime — and dominating production, distribution and exhibition under a vertically integrated system. In 1958, cinema attendances in Japan even reached an all-time high, bringing in 1.13 billion cinema ticket sales. Under this climate, the studios displayed predictable conservatism in order to maintain the status quo, and there was little room for more artistically ambitious films to emerge, especially from outside the studio system — in 1959 for instance, zero independently-produced feature films were released.

And yet, cracks slowly appeared in the hegemony of the studio system. Primarily due to television, which in the 60s instigated drastic declines in cinema attendance; but also, ironically enough, due to a new breed of directors hired by the studios themselves. The growing youth demographic of the 50s had encouraged the studios to start producing youth-oriented pictures, such as Crazed Fruit (1956) — incidentally scored by Takemitsu, we can loosely call it the Japanese ‘Rebel Without A Cause‘. These films’ depiction of hedonistic youths caused uproar in certain sections, but the studios realised they satisfied the demand of younger audiences and kept making them. To keep fulfilling this factory-line production of ‘youth films’, the studios fast-tracked several young, talented filmmakers through their apprentice scheme, giving them the opportunity to direct. These included, at Shochiku: Oshima Nagisa, Yoshida Yoshishige and Shinoda Masahiro; and Imamura Shohei and Suzuki Seijun at Nikkatsu. They would come to be collectively labelled the ‘Japanese New Wave’. Unlike the other 60s new waves however, and unlike Teshigahara, they started from a studio background. The irony is that they would prove to be Trojan horses for the studios, sharing a stance that was staunchly oppositional to the enduring traditions of Japanese cinema.

In 1960, just as the studio system was set to enter a crisis that would forever change the landscape of Japanese film, the political atmosphere was once more simmering with upheaval. Mass demonstrations and protests, in which both Teshigahara and Abe participated, happened daily against the signing of the notorious ‘Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan‘, which effectively sanctioned the continued military presence of US troops.

Japan’s close post-war alliance with the US was also partly the reason for its miraculous economic growth, which reached its symbolic landmark moment with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. But for the rebel filmmakers of the New Wave and for the avant-garde artists alike, Japan was going through a post-war identity crisis on a national scale. The country had not had time to digest the transition after the war, from the extreme expansionist policy of the 30s and 40s when Americans were enemies, to now being a rapidly developing capitalist state sponsored by, and kowtowing to, the US. In the eyes of these socially-conscious artists, Japan was moving too fast, caring only about economic progress without taking time to cater for the less fortunate sections of Japanese society. These sentiments were reflected in the films of the time, and in their recurrent themes of people on the edge of society, alienation and the search for identity.

The New Wave directors would explore many of the same themes as Teshigahara and Abe would, but in very different ways. In comparison to Imamura’s earthy irreverent realism and Oshima’s iconoclastic films about society’s outsiders, Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu’s films were far more allegorical and oblique. Oshima is often labelled the “Japanese Godard”, a moniker which is too simplistic, but accurate in that both infused their films with radical politics and daring formal innovations. As for Imamura, his cinematic goal was depicting the underbelly of Japanese society, the side of Japan which he felt had never been shown in films before, and this is exemplified in all his 60s work, notably Pigs and Battleships (1961). Set in Yokosuka, in the shadow of a US military base, it is peopled by pimps, prostitutes, petty gangsters and generally impoverished people, and was essentially a darkly comic allegory of Japan’s betrayal of its citizens in pandering to the demands of the US.

But the key event of this period was Oshima’s unabashedly political Night and Fog in Japan (1960), which is packed full of political rhetoric and revolves around the demonstrations against the US-Japan security treaty. Deemed too radical and potentially dangerous, it was removed from cinemas by Shochiku studios after just three days. Oshima’s response to this censorship was a simple one, he terminated his contract and resigned from the studio, and his other New Wave contemporaries would follow suit over the next few years. This was the first collapsing domino which would trigger the exodus of the studios’ finest young directors to the world of independent cinema — the studios would never recover from this downfall. Now, despite their different approaches, the likes of Oshima and Imamura on one side and Teshigahara on the other were all in the same boat as independents removed from the studios, and in need of a distribution and exhibition platform.

The Art Theatre Guild (ATG), established in November 1961, initially as distributor and exhibitor of foreign art films and later financing Japanese productions, would go on to fill this gap for Japanese independent films. The ATG represents the juncture between the New Wave agitators who fled the studios’ grip, and the experimental filmmakers coming from a background of avant-garde documentaries and shorts. Building on from previous initiatives, such as Cinema ’57 or the Sogetsu Art Centre, the ATG was more successful as a network supporting independent cinema. Teshigahara himself acknowledged: “You could say that my path to film was opened up within the circumstances of [ATG]’s birth, when those who were cinema’s heretics gained a foothold“.

The ATG, despite being co-owned by Toho studios, helped independents find an outlet for distribution and exhibition, having a total of ten cinemas at their disposal, including its iconic theatre in Shinjuku, a neighbourhood of Tokyo which would become the nucleus of many underground sub-cultures. Thus the ATG was the logical offspring of the meeting between all the cinematic and artistic movements hitherto mentioned, and would act as the catalyst for the Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu collaboration to materialise into feature films. In 1962, thanks to his father Sofu who funded him, Teshigahara had the means to co-finance his debut film, but under the previous regime of the commercial studio system, it simply wouldn’t have been seen by anyone. This is where the ATG’s role as distributor and exhibitor was absolutely crucial because it allowed Teshigahara’s debut Pitfall to be seen by audiences and critics. The rest of the story of the ATG and of the Japanese New Wave is also fascinating, but having fleshed out the context now is the time to zoom in specifically on the slice of 60s Japanese cinema which is this essay’s focus.

A unique collaboration

Cinema is not only received by mass communal audiences, but as a creative process is a fusion of visual, verbal and aural/musical elements, and indeed one could say every other type of artform can be found within cinema in one shape or another, with many artists and technicians all applying their unique talents towards the same goal. Hence it was the logical choice for Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu to realise their goal of a shared artistic experience. Their chemistry meant that each one spurred the other on to greater inspiration: Abe’s complex philosophical ideas required Teshigahara to find the perfect visual metaphor, and Takemitsu’s minimalist music reined in Teshigahara’s natural tendency towards over-expression. Traditionally a film composer would arrive in post-production and compose a score according to the director’s wishes, but not in this case. Teshigahara said of Takemitsu: “He was always more than a composer. He involved himself so thoroughly in every aspect of a film – script, casting, location shooting, editing, and total sound design“. It is therefore not quite right to see each as only having the fixed role of director, writer or composer respectively; rather they should be regarded as a fluid and dynamic team, each individual influencing the work of the two others.

Now is the ideal time to note that, although I regard these three men as the combined auteurs of their films, we should not overlook the contributions of other important members of the crew. For instance cinematographer Segawa Hiroshi or art director Yamazaki Masao, who both worked on the first three films, or Awazu Kiyoshi who designed the title sequences. >But Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu were not just the constants over all four films, but also the most distinguished in their relative fields outside of the filmmaking industry, and thus they illustrate the new openings in Japanese cinema at that time, which is a key part of the story I’m wanting to tell here.

</p It is rare anywhere that people firmly rooted in the world of literature and the arts take up filmmaking with as much success as these men did, and hopefully I’ve conveyed a sense that the methodology of their working relationship was just as uncommon. But now we finally come to the most important part, which is discussing the fruits of their collaboration, the films themselves.

Pitfall (1962)

(Hover mouse over screencaps for extra captions.)

The only collaboration yet to occur by 1962, (Teshigahara-Abe), in fact transpired by chance. Teshigahara happened to see a TV drama, written by Abe in 1960, during the bitter labour disputes at the Mitsui Miike coal mine which it implicitly alluded to. The director, looking for a project to make his debut feature, instantly thought it ideal; he contacted his old friend Abe, who was delighted by the idea and re-invented his television play into a script, which would become Pitfall.

The only collaboration yet to occur by 1962, (Teshigahara-Abe), in fact transpired by chance. Teshigahara happened to see a TV drama, written by Abe in 1960, during the bitter labour disputes at the Mitsui Miike coal mine which it implicitly alluded to. The director, looking for a project to make his debut feature, instantly thought it ideal; he contacted his old friend Abe, who was delighted by the idea and re-invented his television play into a script, which would become Pitfall.

The film intertwines two main story strands: the first a surreal conspiracy thriller (a mystery man chases and kills an itinerant miner, played by the then-unknown Igawa Hisashi, in the arid rural landscapes of a mining village, mistaking him for a local union leader whom he resembles); the second a ghost story (the dead miner returns to life as a ghost in the same place, and meets a community of deceased souls), sometimes punctuated by montages of actual stock footage of mine-fires and mining accidents, reminding us of Teshigahara’s documentary roots, as well as striking visual effects reminding us of his background in fine arts. What makes Pitfall remarkable is its surprising blend of social realism (the miners and unions, the mundane squalid conditions of the mining village) with supernatural elements (all the dead miners and villagers inhabiting a literal ghost-town  alongside but invisible to the oblivious living). Thus Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu managed to realise their long-standing ambitions of expressing a new form of realism (Surreal realism? Supernatural realism? Existential realism?), and true to themselves they make some form of political statement without neglecting artistic experimentation or the philosophical themes close to Abe’s heart.

alongside but invisible to the oblivious living). Thus Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu managed to realise their long-standing ambitions of expressing a new form of realism (Surreal realism? Supernatural realism? Existential realism?), and true to themselves they make some form of political statement without neglecting artistic experimentation or the philosophical themes close to Abe’s heart.

This use of a clash between two seemingly opposing modes of storytelling certainly owes a debt to Buñuel’s Las Olvidados (1950), a known favourite of both Abe’s and Teshigahara’s, for the way it merged documentary style with surrealist and psychological aspects. Pitfall treats the ghost story (without seeking any thrills or frights) in the same objective tone as its socio-political allegory (which is completely without preaching). Teshigahara actually described his debut as a ‘documentary-fantasy’, a mix of Abe’s conceptual ideas and his own eye for great visuals. It’s also a blend of Japanese and Western cultures, influenced by Noh theatre, as much as by Greek myths and tragedy (the ghosts  serve as a “chorus” narrating events, and the concept of ghostly underworld reminds of the Orpheus myth and countless others).

serve as a “chorus” narrating events, and the concept of ghostly underworld reminds of the Orpheus myth and countless others).

Pitfall was symptomatic of a new approach to cinema. Its cast came from the shingeki (‘new theatre’), characterised by a more modern style of acting, and was marked by Teshigahara’s improvisational ethic. His crew, coming from studio backgrounds, struggled to understand his working methods and were often baffled by his decisions to film things not in the script and seemingly not serving plot (e.g. a pack of wild dogs Teshigahara spotted nearby). While Abe and Teshigahara had complete freedom to express themselves, all was threaded together by Takemitsu’s consistently minimalist score, which complements the sparse mining ghost-town setting. Takemitsu used a host of different techniques, like improvising John Cage’s method of the ‘prepared piano’, sounding unexpected, dissonant chords which crash in the middle of a tense silence, and incorporating strange barely recognisable sound effects.

The overall result is an impressively innovative debut, unconventional, ambitious and as rich as one would expect the creation of such a varied trio of artists to be. It’s partly an exposé into the machinations between various mining union factions (probably influenced by Abe’s own experiences with the clashing cliques of the Japanese Communist Party), partly an angry condemnation of the exploitation of mine workers, partly an existentialist ghost story showing the cruel irony of a character who remains isolated and damned whether dead or alive(the title alludes to Abe’s metaphor linking mines and mine-fires with the pit of Hell), and also partly just an outlet for the coming-together of Teshigaraha’s brilliantly inventive visual sense and Takemitsu’s deeply atmospheric soundscapes. It’s also many other things, and would set the tone for the rest of the collaboration’s films in being so multi-layered.

Woman in the Dunes (1964)

For the remainder of their collaboration, the films would be based on Abe’s novels, written roughly a year before the film’s release, which he then adapted for the screen. One of his most celebrated books, the existentialist parable Woman in the Dunes, would provide the basis for their second film and biggest success. Internationally it would be a massive arthouse hit, winning the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes and making Teshigahara the first Japanese director to be Oscar-nominated. As in Pitfall themes of identity and isolation are touched on, but Woman in the Dunes drops the multiple stories to focus on just one narrative with essentially just two main characters.

One of these is an amateur entomologist (Okada Eiji) on a day-trip from Tokyo to some nondescript rural desert. Looking for sand beetles, he loses track of time, misses the last bus back to the city and is left stranded overnight. He is forced to seek shelter in a nearby village, where they duly shack him up with a young widow (Kishida Kyoko) whose house is actually deep in the middle of a quarry, menacingly encircled by the sand, and only accessible by a rope ladder. As he realises that the woman’s life consists of endlessly removing sand to protect her house being submerged by it, he reacts with a mixture of pity and condescension. However, the following morning the rope ladder  is suddenly gone, he finds himself stuck with this woman in the forlorn sand-surrounded house and a journey of discovery begins for him. It shall take him from anger, escape attempts and refusal to help the woman in her daily tasks (which he sees as futile but are actually a matter of survival), to acceptance, co-operation with and even love for the woman, and paradoxically finding some form of existential meaning through captivity. Tellingly it is only at the very climax of the film that we learn the man’s name, when an on-screen police document reveals it, ambiguously suggesting that it is only through resigning himself to his destiny that he regains some identity.

is suddenly gone, he finds himself stuck with this woman in the forlorn sand-surrounded house and a journey of discovery begins for him. It shall take him from anger, escape attempts and refusal to help the woman in her daily tasks (which he sees as futile but are actually a matter of survival), to acceptance, co-operation with and even love for the woman, and paradoxically finding some form of existential meaning through captivity. Tellingly it is only at the very climax of the film that we learn the man’s name, when an on-screen police document reveals it, ambiguously suggesting that it is only through resigning himself to his destiny that he regains some identity.

This document, along with a montage of official forms and street noises during the opening titles, suggesting the modern world of bureaucracy the man has left behind in the city, are the only allusions to urban settings. It is really Abe’s metaphors of the desert and sand that are the crux of the film’s meaning, and we can perhaps trace these images back to his Manchurian experience (in a colonial limbo, neither quite China nor Japan, full of desert landscapes). This  desert is exaggerated both in film and novel, since the Japanese setting contradicts the lack of such large deserts in Japan, and of course nor is the house surrounded by steep slopes of sand physically plausible. This is a universalist treatment, not a realistic one, and gives away more of Abe’s influences. The premise is reminiscent both of Sartre’s play No Exit and of Camus’ Absurdist essay The Myth of Sisyphus, where Sisyphus is given the futile task of eternally pushing a rock up a hill by the Gods but yet finds happiness in his fate. Through this mix of influences, Abe had developed a style quite different from any previous Japanese literary trends. His prose was known for its concise imagistic style which translated well onto film, and cinema’s advantage over literature (its materiality and immediate sensorial stimulation) would be exploited to the fullest by Abe and the trio as a whole.

desert is exaggerated both in film and novel, since the Japanese setting contradicts the lack of such large deserts in Japan, and of course nor is the house surrounded by steep slopes of sand physically plausible. This is a universalist treatment, not a realistic one, and gives away more of Abe’s influences. The premise is reminiscent both of Sartre’s play No Exit and of Camus’ Absurdist essay The Myth of Sisyphus, where Sisyphus is given the futile task of eternally pushing a rock up a hill by the Gods but yet finds happiness in his fate. Through this mix of influences, Abe had developed a style quite different from any previous Japanese literary trends. His prose was known for its concise imagistic style which translated well onto film, and cinema’s advantage over literature (its materiality and immediate sensorial stimulation) would be exploited to the fullest by Abe and the trio as a whole.

Indeed I might have spoken too soon saying there’s just two main characters, as the continuity of images and sounds breathe life into the sand, ubiquitous constant of this movie. Hence Teshigahara’s opening succession of shots, beginning with a single microscopic sand-grain, then a handful of grains in extreme close-up, until we see an actual-size layer of sand, and only then do we figure out what we’ve been seeing. It prepares us for the indelible tactile feel created by Teshigahara’s use of close-ups and superpositions. There are various shots of sand, of sand on skin, of insects on sand, of skin looking like sand or vice-versa. The sand gets everywhere, on skin, in hair, in shoes, even through the fissures of the house’s roof. At times it feels almost liquid, when it avalanches down into the pit or slowly flows down crevices. This is all heightened by Takemitsu’s masterly music, mixing a shrill string ensemble score with other-worldly electronic sounds. As always he also did the sound design, crafting the soft hissing of the sand which constantly rings over the film. We are in an alien world, unsettling and claustrophobic, in part also due to the use of long-focus telephoto lens which compresses the distance between the man and the walls of sand behind him and flattens the image. Audiences were left with the sensation that they too had sand on them, which says all about how well Teshigahara’s technical skill and Takemitsu’s aural architecture brought Abe’s themes to concrete existence.

even through the fissures of the house’s roof. At times it feels almost liquid, when it avalanches down into the pit or slowly flows down crevices. This is all heightened by Takemitsu’s masterly music, mixing a shrill string ensemble score with other-worldly electronic sounds. As always he also did the sound design, crafting the soft hissing of the sand which constantly rings over the film. We are in an alien world, unsettling and claustrophobic, in part also due to the use of long-focus telephoto lens which compresses the distance between the man and the walls of sand behind him and flattens the image. Audiences were left with the sensation that they too had sand on them, which says all about how well Teshigahara’s technical skill and Takemitsu’s aural architecture brought Abe’s themes to concrete existence.

Woman in the Dunes relies heavily on symbolism, with the sand, the sea, insects, and water all having been interpreted in various different ways as having symbolic value. There is no clear agreement on any one accepted meaning, with responses even split as to whether the ending is positive or negative. The sand can be seen as a metaphor for individual lives within a greater collective framework (we are individual grains of sand, in a world whose immense scale we barely fathom), for the human condition and the struggle to accept our destiny (we are the insects in the sand, largely impotent against Fate), or as a fertility allegory and hence backing up the theme of male-female relationships, as slowly the man learns to love the woman. Even perhaps as the currency of financial goods keeping the capitalist world running but which Abe saw as entrapping (the sand is all-invading, all-pervasive and takes control over all around it in an irrational manner). This list is far from extensive, of course sand is also associated with time, or with a prison as in the quicksand our man falls into, we could go on and on… What seems evident is that the man goes on a journey of self-discovery and by the end has accepted his fate, adapted to the situation, and  connects to a sense of community by agreeing to work to help the woman and the villagers. Such a reading ties in with the very Japanese concept of giri, or obligation, as well as Camus’ Sisyphus obviously.

connects to a sense of community by agreeing to work to help the woman and the villagers. Such a reading ties in with the very Japanese concept of giri, or obligation, as well as Camus’ Sisyphus obviously.

The film’s polysemy was the source of a flurry of critical and academic writing about the film in the West, and its reception served as a model for the then relatively new phenomenon, the ‘international Japanese film’. Much of Japanese cinema’s output in the 60s, like much of ‘world cinema’, had come to be defined through international reception and indeed Woman in the Dunes was first sent to festivals before its domestic release. Okada Eiji, the leading actor, had already obtained fame abroad for his previous role in Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959), and thus brought with him an exotic appeal to both international and Japanese audiences. The film also overlaps with another significant trend, characteristic of the Japanese New Wave, namely the increasing depiction of sexuality in comparison to the studio films of the 50s. Kishida Kyoko’s earthy sensuality as the woman gives the film an erotic undertone culminating in the man’s bestial desire. Japanese cinema’s exploration of sexuality in this period ranged from the soft porn produced by the studios to get their foothold back, to the far more explicit films of Oshima who analysed themes of identity and politics through sex. The  earthiness of the woman also recalls the heroines of Imamura, as does the insect imagery. Imamura (for example in The Insect Woman but also in many other of his 60s films) often aligned the resilience of his characters with that of insects. Again this links the trio’s work to contemporaneous Japanese cinema, even if the end products were very different.

earthiness of the woman also recalls the heroines of Imamura, as does the insect imagery. Imamura (for example in The Insect Woman but also in many other of his 60s films) often aligned the resilience of his characters with that of insects. Again this links the trio’s work to contemporaneous Japanese cinema, even if the end products were very different.

Woman in the Dunes was Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu’s artistic pinnacle, both according to general consensus and in my opinion, because the synthesis between the strengths of all three is at its peak and most seamless.

The great Andrei Tarkovsky ranked it as one of his top 10 films, and if one looks closely it’s possible to see its influence on Solaris, as well as that of the trio’s next film The Face of Another. This next film would question even more literally how free we really are, and to what extent any individual identity is just a captive of conventions and restrictions depending on factors beyond his/her control.

The Face of Another (1966)

Abe adapted The Face of Another from his own novel, a seemingly unfilmable stream of consciousness narrated in first-person, and despite the success of the relatively linear Woman in the Dunes, the script returned to a more complex multiple-narrative structure as in Pitfall. On top of this, they moved for the first time to an urban setting, and Teshigahara somehow managed to employ even more cinematic tricks than in the previous two films put together.

Abe adapted The Face of Another from his own novel, a seemingly unfilmable stream of consciousness narrated in first-person, and despite the success of the relatively linear Woman in the Dunes, the script returned to a more complex multiple-narrative structure as in Pitfall. On top of this, they moved for the first time to an urban setting, and Teshigahara somehow managed to employ even more cinematic tricks than in the previous two films put together.

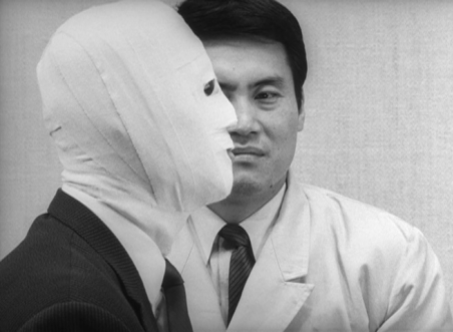

The plot tells of a chemical factory employee called Okuyama (a riveting performance from star Nakadai Tatsuya who’d already been in Yojimbo, Harakiri and When a Woman Ascends the Stairs), who has suffered disfiguring burns in an industrial accident. A mysterious surgeon called Dr K (a probable Kafka nod), offers him a state-of-the-art solution by giving him a face transplant, where the facial ‘mask’ is a donor’s actual face — a prescient idea which was still sci-fi in the 60s but has very much become reality today. Thus armed with literally the face of another and coming back into society as a “new” person, Okuyama sets out to woo his estranged wife, although he feels uneasy about her potentially falling in love with someone who, to her, is another man. This naturally sets up an exploration of identity, and how a transformed physical appearance might impact inner personality. Abe had always been deeply  interested by the causal relationship between social identity and personal identity, how social contracts shape personality, and how individual identity can hope to survive within mass conformist society. So Face of Another represents a culmination of some of his most essential themes.

interested by the causal relationship between social identity and personal identity, how social contracts shape personality, and how individual identity can hope to survive within mass conformist society. So Face of Another represents a culmination of some of his most essential themes.

Teshigahara again finds images to enhance Abe’s philosophical overtones about divided identities and double personalities. Visual rhymes recur across the film, similar actions and scenes are repeated in subtly different ways. Shots of mirrors, masks, split faces and reflecting surfaces abound. “What really lies beyond the skin-deep?” is the question the film seems to keep prodding at us. And the narrative itself has a mirror, in its parallel strand of a young woman’s tale (in the novel this was a movie Okuyama watched). She too is disfigured, facially scarred by nuclear radiation in WW2, but her world is unconnected to Okuyama’s and the two never interact; instead her story is there to act as doppelganger to his, and make us ponder the similarities and contrasts in their relative fates.

Face of Another can even be said to have a third narrative branch, as the scenes inside Dr K’s office obey a dreamlike logic of their own, not quite belonging in either the world of the young woman nor in that of Okuyama’s daily life. This bizarre clinic, full of changing objects, body-parts, diagrams, surfaces and structures, reflects character psychology rather than any realistic setting. It seems to be a mental space, perhaps in Okuyama’s psyche, and hints at the possibility that Dr K might be his imaginary alter-ego. In any case it once again highlights the radical imagery Teshigahara had in his locker. Fittingly in the spirit of inter-arts collaboration, it was designed by his close friend, the famed architect Isozaki Arata, and is as memorable a piece of set design as you’ll find in 60s cinema.

Face of Another can even be said to have a third narrative branch, as the scenes inside Dr K’s office obey a dreamlike logic of their own, not quite belonging in either the world of the young woman nor in that of Okuyama’s daily life. This bizarre clinic, full of changing objects, body-parts, diagrams, surfaces and structures, reflects character psychology rather than any realistic setting. It seems to be a mental space, perhaps in Okuyama’s psyche, and hints at the possibility that Dr K might be his imaginary alter-ego. In any case it once again highlights the radical imagery Teshigahara had in his locker. Fittingly in the spirit of inter-arts collaboration, it was designed by his close friend, the famed architect Isozaki Arata, and is as memorable a piece of set design as you’ll find in 60s cinema.

Equally memorable (as ever) is Takemitsu’s score combining the eerie tones of glass harmonica with strangely menacing Germanic waltzes over both the opening and closing credits. This culturally jarring choice of Germanic music is subtly backed up elsewhere in the film, in the use of an electronically distorted Hitler speech in Takemitsu’s sound mix, or in the recurring setting of Munich-style beer halls (obviously a reference to the type of location in which Hitler infamously rallied support in the 1920s). Add to this the physical remnants of the war on the girl’s face, and it is painfully clear how the spectre of WW2 looms over this tale of identity crisis, to remind us that this crisis is a 20th century malaise, linked to the calamities man has spread on the planet, and to the challenges in continuing to have faith in humanity.

Equally memorable (as ever) is Takemitsu’s score combining the eerie tones of glass harmonica with strangely menacing Germanic waltzes over both the opening and closing credits. This culturally jarring choice of Germanic music is subtly backed up elsewhere in the film, in the use of an electronically distorted Hitler speech in Takemitsu’s sound mix, or in the recurring setting of Munich-style beer halls (obviously a reference to the type of location in which Hitler infamously rallied support in the 1920s). Add to this the physical remnants of the war on the girl’s face, and it is painfully clear how the spectre of WW2 looms over this tale of identity crisis, to remind us that this crisis is a 20th century malaise, linked to the calamities man has spread on the planet, and to the challenges in continuing to have faith in humanity.

These themes bring us back to the comparisons I mentioned in the intro, which typically align the trio’s films with the European modernists of the period (Bergman, Resnais, Antonioni, etc). Out of the four, Face of Another is the film for which this rings truest. The post-war malaise in Europe was also the primary factor in the 60s films of these European directors. An even more direct comparison can be made to another masterpiece made in the same year, Bergman’s Persona. Visually: in how Bergman, like Teshigahara, often frames the faces of his two protagonists, alter-egos of each other, in the same shot: example. Thematically, in the two films’ shared notion that human interaction is necessarily an imperfect masquerade, a performance projected by a facial mask to the outside world, which loses some authenticity on the way from initial mental conception to actual physical realisation. The fact Face of Another was tapping into a vibe already well-trodden by European cinema (and remember how in vogue the European modernists were internationally at the time), largely accounts for its poor reception outside Japan. Western audiences were already very used to such themes from European directors and expected something more like Woman in the Dunes again.

To be fair, almost any film would struggle to follow up a work as beguilingly unique as Woman in the Dunes. But once Face of Another is allowed to step out of its predecessor’s shadow, it holds up on its own merits as an incredibly enigmatic and visionary film, dabbling in sci-fi and horror yet remaining one-of-a-kind. It is also the most self-referential of the trio’s films, in that actors from both the previous two films appear in it, and there are brief on-screen cameos for Abe, Takemitsu, and even the instrumental Sogetsu Art Centre where Teshigahara filmed the final scene.

It may not have the unforgettable symbolism of the sand and desert of the previous films, but it makes the most of its Tokyo backdrop, often showing shots of new buildings and construction sites, reminding us that Tokyo itself has undergone a “facelift” and identity-change during the economic boom. This metaphor connecting man’s identity with that of the modern city would be pushed to an extreme in the trio’s fourth and final film together.

The Man Without a Map (1968)

The trio’s final film together, The Man Without a Map, was both their first in colour and in widescreen CinemaScope. This switch from more classical black-and-white and 4:3 aspect ratio came about because Man Without a Map had more studio involvement than any of the previous films, essentially being a vehicle for actor Katsu Shintaro, already a household name for playing Zatoichi in the popular film series. It remains the least known of the four films outside Japan, particularly due to a rights dispute which forbids the film from being released on DVD with subtitles, and hence has never been released for home viewing outside of Japan (but home-made subtitles are available on the internet).

This is a good opportunity then to re-evaluate this ‘forgotten’ film alongside the other three. If their previous films had taken certain horror and sci-fi clichés as starting points, Man Without a Map is (on the surface) more recognisably a ‘detective film’, but knowing Abe by now, his novel and screenplay were never going to be conventionally generic. Initially at least, Katsu’s character is the cliché of the hard-boiled loner private-eye, whose job is his life. He is hired by a woman to find her missing husband, a 43-year-old employee at a car manufacturing company who has not been seen for 6 months. As we could expect, there follows an array of sleazy characters (lots of good performances from the whole cast), a shady criminal organisation and a potential love-interest with the lonely wife/client, but none of these feel like the detective-film tropes they’re riffing on. This is because the detective storyline is secondary, and as the investigation fumbles along from one red herring to the next, the plot gets too confusing to keep up with and our attentions switch to the metaphysical nature of the detective’s search. Of course, that’s exactly the point.

The allegorical map of the title, which our confused detective indeed clearly does not have, refers not only to a map of the city but to a map of the internal self too, and on both counts he is lost. In one scene he identifies with (and starts talking to) the corpse of a dog lying on the road, run over by oncoming traffic (symbol of mass technological society) and bruised and battered just like our detective is. As he delves further into the Tokyo underworld, there is a sense that he is also discovering the recesses of his own mind (hence some telling dream/fantasy sequences), until eventually he begins to assimilate traits of the missing man he is seeking. It is a quite literal display of the fragile malleability of identity, and harks back to the essence of Abe’s work. Pitfall and Woman may have played out in desert settings, but Abe’s depiction of the city has the same function in the next two films, as an existential no-man’s-land, where, despite being surrounded by more and more people, city dwellers in fact only feel increasingly alone. There is no place left for individuality amid the immensity of an urbanisation rapidly developing over the ruins of a sinister war-time past which were not properly dealt with. In Abe’s view, the result is an immense emptiness, completely impersonal and soulless, and hence to be compared to a  barren desert.

barren desert.

The strength of the film’s theme is that Abe could not have asked for a better real life epitome of all his major themes than the phenomenon of disenchanted people suddenly disappearing from their daily existence without trace, an identity literally going missing. It must be stressed that this was a serious social problem in 1960s Japan, with many thousands of cases each year, and Abe was one of the first to make it the subject of artistic inquiry – explicitly in The Man Without a Map, but also implicitly in Woman in the Dunes. The implication is that these were people fed-up of their daily routines who ‘escaped’ society by leaving everything and starting a new life (a new identity) somewhere else. A comparison must be drawn with Imamura’s complex documentary A Man Vanishes (1967), which explored the same issue but in a very different manner, yet another sign that Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu tackled the same themes as other directors, only in their own unique way.

Although the stylistic experimentation is relatively subdued compared to the previous films, Teshighara once again visualises Abe’s ideas in interesting ways. Aerial views of labyrinthine roads and highways mark the widescreen compositions, and a visual scheme of gaudy yellows and menacing reds is employed to attack our senses. The city is itself a character much like the sand was in Woman, certainly less effectively, but the many disorienting shots of the cityscape and the constant flux in background or foreground of moving cars, crowds or trains, go some way to suggesting the rootlessness of modern society. The way this counters the inertia of our detective as he goes nowhere (his investigation leads to dead-ends or  goes in circles) is one of the strongest elements of the film.

goes in circles) is one of the strongest elements of the film.

But the biggest flashes of brilliance arguably come from Takemitsu, not least the way he intercuts samples of Elvis Presley’s I Need Your Love Tonight, with Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in C Minor. These speak to his Western tastes, but his use of haunted silences come to him from the Japanese influence of the concept of Ma – the importance of counterpointing form with emptiness in art – and allowed him to bring scenes to life with a sudden slash of sound. His fusion of avant-garde musical techniques, of spare minimalism adding another dimension to the film rather than repeating what its images were already saying, and of taking inspiration from real every-day sounds, made him a pioneer of the movie soundtrack. His direct influence can be felt even to this day; I’m thinking particularly of Jonny Greenwood’s scores for Paul Thomas Anderson, where the affinity is evident.

Concluding Remarks

After The Man Without a Map, Teshigahara eventually took over his father’s ikebana school at Sogetsu, and put any cinematic projects on the back burner. In 1972, he would make his first feature not scripted by Abe, Summer Soldiers, which was more explicitly political than the collaborations and less successful. After that, he would only direct three further films until his death in 2001, including Antonio Gaudí (1984), a visual documentary dedicated to the architect who had inspired him so much in his youth. Going their own ways, Abe and Takemitsu both cemented their reputations in fields other than cinema. Despite never all collaborating on a film together again, the three of them remained ‘renaissance men’; Teshigahara was, as well as a filmmaker, a painter, sculptor, potter, calligrapher, ikebana master, interior and garden designer and impresario of avant-garde meetings and activities; Abe was a novelist, playwright, poet, theatre director, philosopher, essayist, political activist, photographer and director of a few short films; Takemitsu was composer, poet, musical theorist, wrote detective stories and even had a stint as celebrity chef on Japanese TV!

These three artists always resisted pigeon-holing into any one artistic domain, their creative instincts as universal as their films. Hopefully this essay goes some way to reassessing an unjustly overlooked filmmaking trio, as well as their origins in the context of post-war Japan; their attitude to art and how it should help transform society; and their desire to transcend boundaries and barriers, to blend Western influences with Japanese ones, the political with the artistically experimental, and realism with the more fantastical. All this in an era of transition for Japanese cinema, which meant they were allowed to experiment to their hearts’ content, each bringing from their respective fields an unconventional quality that cinema had seldom seen. To put it very simplistically these were: Abe’s existential themes, Takemitsu’s modernist minimalist sounds, and Teshigahara’s documentary-style surrealism. Despite some connections to the Japanese New Wave and even to other experimental or avant-garde cinemas, these elements combined to produce a cinematic style unlike anything before or since, and their films remain a testament to cinema being the perfect artform to showcase the true alchemy of Art. (Jean-Baptiste de Vaulx, December 2013)

This is an excellent essay, I had never appreciated the depth of collaboration and how fluid their roles were. It’s hard to know where to begin. As you say the big theme is that these films are responding to a postwar crisis of identity. It’s put so well in ‘The Face of Another’ how we simultaneously put on social masks to conform and join society but those same masks are barriers to each other and we lose our individuality/personal identity.

Just a general observation, is a reason why these films appeal to us today because in some ways aren’t we going through our own identity crisis, also spurred by America? With the internet we are being encouraged more forcefully than before to put on “masks”, exemplified by social networking profiles that are in no way true reflections of ourselves, and abandon our individuality and speak the same way (‘yo’), watch the same things, buy the same products. Our social identity is supplanting our personal identity.

The point that the doctor is like a psychological construct of the masked protagonist in The Face of Another, that he is an alter-ego, is very interesting. It prompts me to think a Jungian reading of the film must be very fruitful.

Thanks for the comment! Some interesting questions there, definitely Abe was deeply interested in the effects of mass consumer society (which to him had come to be represented by America, as a construct if not as an actual geographical place) on individual identity. It’s fascinating to think what he would make of things now, when we’re entangled in a technology that has much potential for exciting creative things, but also so much for things that are as you say superficial, skin-deep and conformist.

I wonder, today where are the great films or even novels addressing such issues in ways that are as interesting as these works of 50 years ago were? Every time I ask a question like this I’m always reminded of Soderbergh’s words “Cinema just isn’t that culturally significant anymore” and of course he’s pretty right. But still, technology, gadgets and the internet are now such a huge part of how we live and experience the world around us, seems the kind of thing those filmmakers who still think cinema has something to say should want to try to say something about…

Hope you’re gonna write that Jungian analysis of Face of Another!

I just found your blog the other day and am really enjoying it. What a great essay this is!

I’d seen Teshigahara’s trilogy of Abe adaptations, but only recently read and watched The Ruined Map/The Man Without a Map. It’s so odd to see Teshigahara in color, and with a bold, swirling palette.

I love your thoughts on Takemitsu’s opening soundtrack. It’s haunting. That alongside the credit sequence really prep you for a ride that I found pretty darn different from The Woman in the Dunes.

The lovemaking sequence towards the end is the starkest comparative moment between the two films for me. The tight close-ups, breathing and rustling dominating the soundtrack…it’s so intimate, but neither depictions feel anything like love.

Thanks a lot for the kind words and I’m glad you enjoyed the essay 🙂 These were four great films which I really enjoyed watching and writing about. All of them are unique in their own ways and Man Without A Map was no different, that’s what’s so great about them!

Your blog looks pretty fantastic btw, I’ve been checking it out and really happy to see some pieces on Lee Chang-dong’s films! I’m actually just writing a profile piece on him at the moment which should be done soon.

Thanks, Giovanni! I really look forward to your piece on Chang-dong. His work has blown me away. I hope to catch Green Fish soon.

Wonderful article, up there with the one on the documentaries of Adam Curtis. Of course much more work went into this, the breadth of historical/socially inspiring knowledge is tremendous, it ain’t qualitatively better tho.

Haven’t seen any of these films, that will soon be corrected. The Face of Another and Man Without A Map are the most appealing to me, think it probably important to see all of them in sequence tho.

Cheers for your amazing articles, don’t think you could find better anywhere

Thanks very much, glad you find it interesting, let me know what you think of the films when you watch!

Hi! Greets from China. I’m Olga Zhang, program coordinator of World Organization of Video Culture Development. We are an NGO based in China, dedicate to promote prominent films and videos, by creating a platform for screening, research and dialogs.

Your article is amazing and deeply help me understand Japanese and especially Teshigahara Hiroshi’s film. I’m writing to ask whether you can approve us translating this essay.

The theme of our autumn quarterly screening is transform, concerning the filmic adaptation of literature and transcoding between textual and filmic languages. We are going to screen Women in the Dunes in this weekend. This essay has very interesting idea and interpret the director and the film on wise eye which will inspire studies of the film. We want to translate this essay for our Chinese audience as well as promote our pending screening activity.

We’ve translated many works from film critics and researchers as well as journals from filmic websites such as IndieWire, Cinema Scope and Indie Cinema Magazine. If you can permit us translating it, we would have it professionally translated and post it on our website. Due to word limit, there might be a bit deletion for the republication, but we will make sure it is proofread and translated as accurate as possible. It will be publicly accessed. We’d indicate the copyright and resource belong to you. We will attach the original link at the end. We’re willing to discuss if you have any extra requirement.

Our audience are mainly students and artists interested in visual arts and videos. We believe it would be a good publicity in China for Teshigahara’s film and providing various perspectives for research into his works, as well as provoke more study of filmic adaptation.

We’re looking forward to hearing from you. Thank you!

My regards,

Olga

Hi! Greets from China. I’m Olga Zhang, program coordinator of World Organization of Video Culture Development. We are an NGO based in China, dedicate to promote prominent films and videos, by creating a platform for screening, research and dialogs.

Your article is amazing and deeply help me understand Japanese and especially Teshigahara Hiroshi’s film. I’m writing to ask whether you can approve us translating this essay.

The theme of our autumn quarterly screening is transform, concerning the filmic adaptation of literature and transcoding between textual and filmic languages. We are going to screen Women in the Dunes. This essay interpreting his films on wise eye. The idea of your essay is very interesting and inspiring for studies of the film. We want to translate this essay for our Chinese audience as well as promote our pending screening activity.

We’ve translated many works from film critics and researchers as well as journals from filmic websites such as IndieWire, Cinema Scope and Indie Cinema Magazine. If you can permit us translating it, we would have it professionally translated and post it on our website. Due to word limit, there might be a bit deletion for the republication, but we will make sure it is proofread and translated as accurate as possible. It will be publicly accessed. We’d indicate the copyright and resource belong to you. We will attach the original link at the end. We’re willing to discuss if you have any extra requirement.

Our audience are mainly students and artists interested in visual arts and videos. We believe it would be a good publicity in China for Teshigahara’s film and providing various perspectives for research into his works, as well as provoke more study of filmic adaptation.

We’re looking forward to hearing from you. Thank you!

My regards,

Olga

Hi Olga, thank you for your interest. I’d be happy for you to translate my essay. Will it be into Mandarin? Do keep me updated on the process, thanks!

Hi, it’s Olga.It is Mandarin.

Thank you very much!

Hello — Remarkable essay on the Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu collaboration. I am researching Teshigahara’s “The Face of Another,” and there is not much literature available, so I would like to cite your essay. However, I am confused about the authorship of the essay. In the “About” section of the Cinescope website, it mentions Jean-Baptiste de Vaulx. However, in this comment thread, Giovanni Battista seems to say he is the author. If possible, please let me know who I should cite as the author of this essay. Thank you.

Valerie Pires (Film and Media Studies, Columbia University)

Thanks very much for reading and glad you found it of interest. My name is Jean-Baptiste de Vaulx, the ‘Giovanni Battista’ is my username and is more informal. Out of curiosity, what exactly is your research about? Would be interested to know!

Thank you so much for the prompt reply. Very much appreciated. My paper proposes something you mention in your essay, that Mr. Okuyama and the Psychiatrist are representations of a sole individual. In other words, I argue that Okuyama and the Psychiatrist are the ego and alter-ego, respectively, of the same man. I explore that possibility through a psychoanalytic perspective. To be precise, though a Jungian lens. I found your essay very helpful as it provides interesting historical context. Thank you.

Valerie Pires (Film and Media Studies, Columbia University)

Sounds really interesting, best of luck with it!