Lucky Luciano (Francesco Rosi, 1973)

In my piece on biopics, I listed examples of biographical films that steer away from convention. Francesco Rosi’s films about legendary mafioso figures (particularly Lucky Luciano and Salvatore Giuliano), with their oblique approach to the biography genre, easily belong on that list, so so I make amends for the earlier omission here.

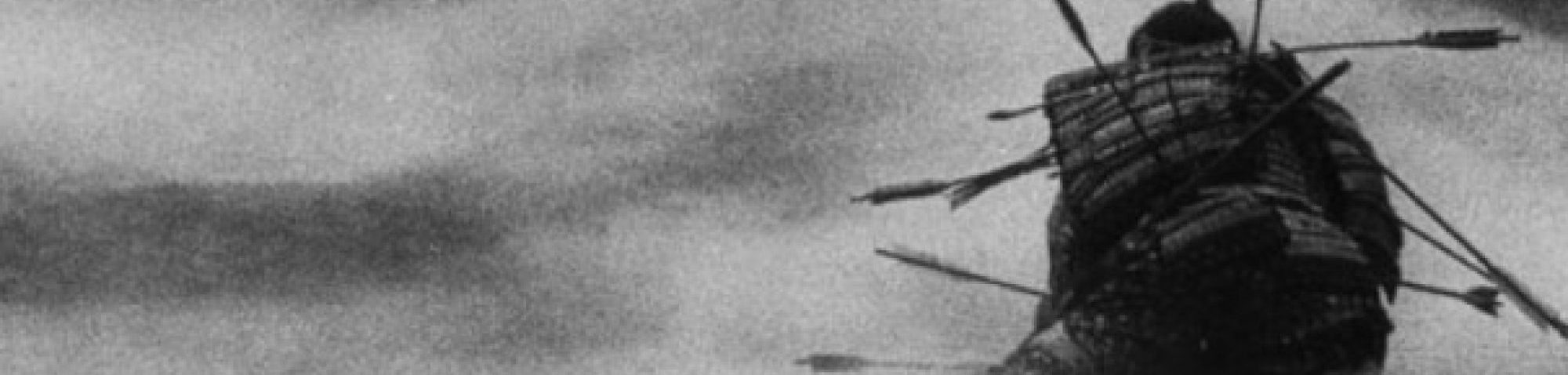

Rosi’s first mature masterpiece was Salvatore Giuliano (1962), the film in which his style, shaped by neo-realism yet bent to his own purposes, truly crystallised. From the title, you might expect a straightforward biopic of the notorious Sicilian part-bandit, part-folk here, shot dead by police in 1950 and leaving behind a disputed and divisive legacy. Yet the film upends such expectations. We barely glimpse the face of the actor playing Giuliano more than a couple of times. Rosi shows little interest for Giuliano’s private life or individual milestones. Instead, Rosi’s gaze encompasses a whole society, a whole system and its institutions, and the tangled web of endemic deceit and corruption that runs through them. That is the true subject of his biopics.

Salvatore Giuliano offered us a panorama, taking in citizens, police and judiciaries, figures from every walk of life, all in some way affected by the mystery of Giuliano’s actions and death. Corruption and shady dealings cloud the facts with uncertainty, creating an investigative narrative almost in the style of Citizen Kane, but one theme asserts itself with clarity: the deep traces of Italy’s North-South divide. Rosi himself hailed from the South (from Naples) and this was a recurring motif in his work, connected as it was to a political dimension: the post-war period of Italy’s USA-sponsored ‘economic miracle’ was the time when prosperity deepened inequality, stretching the rich-poor divide between affluent, industrial North and increasingly left-behind South.

These concerns are all there again in Rosi’s Lucky Luciano (1973), another nominal biopic of a notorious crime figure in Italian history. Born in Sicily, but rising to the top of the mob in New York City by eliminating all his rivals in the 1920s and 1930s, Luciano stands infamous in the history of mobsters. He oversaw the modernisation of the mafia from a small-time family-run affair to a corporate syndicate of global crime armed with significant political and economic clout. But Rosi once again subverts the personal aspects of the biopic or gangster genre, by de-centering the narrative away from Luciano as the sole point of focus, and conducting nothing less than a filmic investigation, complete with extensive research, into the wide-ranging implications and reverberations of Luciano’s crime empire.

This time, the central figure is played by an acting heavyweight, Gian Maria Volonté, unrecognisably subdued in his performance, so we at least see more of him than we did Giuliano. But nonetheless he is at the edges of his own biopic, not much more than a cipher, his face enigmatically blank and rarely showing more expression than a faintly ominous smile behind its image-conscious sheen. This elusiveness works in making him distant, not only from the narrative spotlight, but also from the federal agents who fail to make any charge stick, Luciano by now a master at concealing his nefarious activities, from murder to global narcotics trade, so that nothing ever leads back to him.

Most of the film takes place post-1946, after Luciano was acquitted from a 30-year jail sentence, thanks to a secret deal with the U.S. government, and extradited to Italy. Rosi’s prime interest is history, the history of post-war Italy, the era of the economic miracle, of car manufacturer Fiat and its role in booming industrialisation, and particularly how it, American involvement, and big-time crime like Luciano’s, were all inextricably connected. During the war, the U.S. authorities sought mafia help from Luciano among others to protect the docks of New York City, which were under the tight control of crime bosses, in fear of sabotage or attacks. They also extended their ties with the mafia by paying them to ensure smooth embarkation for their military forces in Sicily, and this alliance extended into the post-war period. As a reward, Luciano’s prison sentence was cut drastically short by Governor Thomas Dewey. Politics, business, and the army, Rosi insists in his systemic panorama, were not merely brushing up against the criminal underworld but absorbing its rot, allowing it to fester at the very core of post-war institutions.

This history, of organised crime and corporate capitalism developing in tandem, is also the subject of Coppola’s first two Godfather films of course, which were released on either side of Lucky Luciano, in 1972 and 1974 (Coppola, much like Scorsese, was surely at that time under the influence of Rosi’s work). But whereas Coppola and Mario Puzo afford the Corleones moments of pathos, letting us empathise and identify with even the most morally corrupt of them at various times, Rosi is extremely careful to avoid this and this is what ends up making Lucky Luciano a radical film.

Rosi is fully aware of Luciano’s mythologised status as a mastermind of crime. There’s a moment when U.S. sailors enthusiastically ask him for autographs, and Rosi even incorporates the strange episode of a Hollywood movie mogul’s failed attempt at turning Luciano’s life into a movie. But this is the antithesis of what that individualised biopic might have been, as Rosi deliberately gives zero psychological depth to Luciano, strips him of any glamour or romantic allure, and makes sure our thoughts never wander into considering how it might feel being in his shoes. Luciano is just a cog in a vast machine of greed and power, and whether the name is Giuliano, Luciano, Capone, or any other mob boss, it makes no difference to the larger design. What Rosi maps out here are the patterns, the relations, the operations, between U.S. and Italian politicians, a U.S. Army colonel who fraternises with Luciano, business associates, other crime heads, lawmen, UN delegates, the pathetic informer (played by Rod Steiger, who’d already starred in Rosi’s Hands Over the City) who feels Lucky’s grip tightening around him.

These characters and many more go into making this political exposé of Power and its entangled tentacles. Every scene feels like a piece of the jigsaw, and it is up to us to put it together. The remarkable thing about Rosi’s films is that for all their intellectual rigour, they are not theses delivering out rigid truths to the audience. There’s a palpable sense of mystery and unknowability, perfectly insinuated by Piero Piccioni’s tempo-switching opening and closing theme that manages to be both menacing and funky. Rosi poses questions without pretending to hold all the answers, insisting that we take an active role, pursuing our own inquiry beyond the frame. His approach to the biopic was unlike any other; it is difficult to imagine a producer green-lighting such a project today, but it is gratifying that Rosi’s biopics still exist, and still call out to be watched and rewatched as an invitation to investigate rather than as diluted and formulaic renderings of complex lives. (June 2015)

2 thoughts on “Viewing Diary: Lucky Luciano (Francesco Rosi, 1973)”