Compared to my 2014 list (here) there seems to be less Hollywood films and less films which made their mark at Cannes, probably telling us little more than that the ‘usual suspect’ directors on both sides of the Atlantic were having a sabbatical. Overall it was still a rich year. There were some surprises, some welcome returns from great filmmakers, and only a few disappointments. If there’s any patterns among the best films of the year, it’s a mix of a wish to re-narrate old historical narratives (and genres, especially the Western and noir), and as can be expected a focus on the worldwide financial crisis and austerity era.

20. Mia Madre (Nanni Moretti)

Overstrung film director Margherita (a fine, controlled performance from Margherita Buy) is working on a socially conscious drama about striking workers. But she has much else on her plate: a buffoonish Hollywood actor (John Turturro nails the part) whose ego she needs to mollycoddle just so he can remember lines; a teenage daughter who doesn’t feel she can confide in her; a break-up with a lover who feels hard done by; and, most of all, the slow death of her ailing mother. Understandably, Margherita fails to juggle everything, and between the difficulties in her real, personal life and the struggles of making her fictional film work, she loses her bearings – as in the anti-austerity banners at her mother’s hospital which remind her of those of the strikers in her film, or during several memory flashbacks and nightmare scenes. But no melodrama or manipulative moments of emotion here, all this is integrated into an understated mix of comedy and tragedy with an assured soft touch by Nanni Moretti, as well as a wryly meta dimension lurking just under the surface. A welcome return of Moretti’s best form since The Son’s Room.

19. The Measure of a Man (Stephane Brizé)

Deserving winner of the Best Actor prize at Cannes, Vincent Lindon’s often-silent but always expressive performance as Thierry, a 50-something everyman trying all he can to get back into employment 18 months since being made redundant, completely anchors this low-key realist drama (Lindon is also the only professional actor in the cast). Initially The Measure of a Man offers itself up for comparison to fellow austerity-era work-drama Two Days, One Night or Laurent Cantet’s fantastic study of an unemployed man spiralling into crisis Time Out (and even perhaps to early Breaking Bad since Thierry like Walter White has a son with CP and is going through a spell of having is ego trampled on).

It comfortably manages to become its own film however, especially after one of its typically elliptical cuts takes us forward and Thierry has a job working in the security department of a giant supermarket – it’s now that the central moral dilemma really kicks in. Director Stephane Brizé makes the film never less than engrossing by splitting most scenes into single long-takes, with the subtle inter-relations and usually off-screen drama playing themselves out in one go to great effect. What makes a life, what makes a successful life-work balance and what makes a job that gives one’s life self-worth, the film seems to ask, and in today’s economical-social context these are deeply relevant questions.

18. Theeb (Naji Abu-Nowar)

The feature debut of British-born Jordanian filmmaker Naji Abu-Nowar, Theeb is a sort of Bedouin Western, a Lawrence of Arabia with its perspective shifted to the local tribes, with some of the suspenseful battle for survival of Deliverance thrown in. The titular young Bedouin boy (‘theeb’ means wolf in Arabic) lives in the secluded but dangerous desert region of Hejaz (modern-day Saudi Arabia) in 1916. After a mission to escort a British soldier through inhospitable territory goes terribly wrong, Theeb is left having to learn to grow up and fend for himself much faster than otherwise needed.

Theeb is a coming-of-age story, albeit one with a unique flavour, and the film limits us to the boy’s perspective. The camera is always on him and we are essentially as oblivious to the wider History of WW1 happening around him as he is. This has the effect of honing us in on his elemental fight for survival, his accelerated mastery of his own wits and judgment, and his overshadowing need for a father figure. Crucially Jacir Eid Al-Hwetiat, a young local boy with no previous acting experience, is a revelation in the attention-commanding central role.

The film’s other main star is the desert itself, its spectacular landscapes and painterly fire-lit night scenery reminding us of another 2015 highlight and modern update on the Western, Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja. But Theeb also has wider lessons for us. Partly a subtle historical one about the birth of the modern Arab world at the juncture between the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of British involvement in the region. But also one demonstrating the opportunities for new stories to be told in today’s era of transnational co-productions. Abu-Nowar is joining the likes of Palestine’s Hany Abu-Assad (Omar, Paradise Now) as an Arab filmmaker getting relatively widespread distribution, and, with European backers now collaborating with Qatari and UAE funding, is this the start of an Arab film renaissance?

17. Jauja (Lisandro Alonso)

Alonso’s mysterious, deconstructed Western set in 19th Century Argentina is a film that stays with you, the kind of film that only gets embellished as your imagination and memories goes to work on it. I already wrote a longer review of it right here.

16. Eden (Mia Hansen-Love)

Every generation searches for some defining event or movement, around which they can inherit some sense of belonging. Just as for their parents it might have been May ’68, for the French youths of the 1990s the watermark moment was the ‘French Touch’ dance/house scene of the nineties. Mia Hansen-Love manages to faithfully and delicately guide us through a tour of this scene, centering around the character of Paul (Felix de Givry), based on her own brother’s ups and downs trying to make his dream career of DJ a reality. Here too there are highs and lows, and ultimately the paradise Paul and his cohorts seek in dance music is ephemeral and the comedown inevitable — that is unless you are Daft Punk, superstar duo to contrast with Paul’s own failing two-man act, and whose anonymity feeds a recurring in-joke in the film.

Paul’s subdued but generally likable personality is also mirrored in the camerawork and laidback storytelling style. This epic chronicle covers 20 years, in which Paul’s friends and entourage form a microcosm of a whole generation, but the most dramatic moments happen just off-screen, and the passage of time is never ostentatiously pointed out. Rather scenes wash over the previous one (and it’s particularly through this trait that we recognise Hansen-Love as a disciple of Hou Hsiao-hsien), leaving the film free of any nostalgia but simply advancing via various slice-of-life scenes through the whole era, aurally earmarked by various tunes house aficionados will recognise and appreciate, before the cumulative emotional effect sneaks up on you once the film is over.

15. Black Coal, Thin Ice (Diao Yinan)

Another film that, like Jauja, stayed with me throughout the year even though I saw it early, this superior neo-noir reinvigorates the genre elements with its chilly Northern China setting, its ultra-tense set pieces and inventive handling of plot structure (one shot/reverse-shot cut taking us forward five years in time stayed with me but there are many other examples). My longer review was already posted here.

14. Dreamcatcher (Kim Longinotto)

The wonderful documentarist Kim Longinotto (Sisters in Law, Divorce Iranian Style) has made creating inspirational portraits of strong, tough women fighting against oppressive circumstances her life’s work. Dreamcatcher is another powerful addition to her filmography, casting her humane, inclusive and never-judgmental lens at Brenda Myers-Powell, an ex-prostitute who now volunteers on the streets of Chicago to help and rescue women in the same situations she once was in. We see Brenda restore hope and self-love to women who’ve suffered lives marred by drug addiction and abuse at the hands of pimps and other men, but Brenda doesn’t even stop there: she goes into schools and prisons, to educate and incite change as best she can in whatever way she can.

The way both Brenda and Longinotto, with her unintrusive directorial presence, gently coax people to open up to them, even with a camera filming, is what makes this such an engrossing documentary. All the stories are presented without any hint of condescension, but in the end this is a celebration of one inspirational fighter. Brenda turned her life around and is now committed to providing every change for other vulnerable girls, in whom she inevitably sees her younger self, to do the same and be a survivor. Along the way Longinotto also shows us Brenda in her quieter more personal moments (she is now married and has a child, and lives in the suburbs), relaxing with her adopted son or choosing which of her wigs to wear based on which personality she feels like on the day. Moments like these also give us a sense of how hard she works at being the person she knows so many out there need her to be, a tireless combatant for local and real positive change.

13. Bitter Lake (Adam Curtis)

I’ve written in more depth about the uniqueness and importance of the work of Adam Curtis, right here, but his sprawling epic chronicling a modern history of Afghanistan, Bitter Lake, seemed like his boldest and most experimental yet. Less narration, less talking heads, a lot more associative editing, made this closer to an essay-film than anything he’d done before, but the trademarks to admire in his previous work are still here intact too. The understanding that narratives are hijacked by those in power and the need for new stories told in new ways: that’s what Curtis has always been about, and in this salient portrait of the complex and multifarious history of Afghanistan, he does not disappoint.

As ever the connections are mind-dizzying, from F.D. Roosevelt, to Saudi Arabia, to the Taliban, via the Soviet invasion and the mujahideen including a young Bin Laden… Afghanistan and its tragic story clearly holds much for anyone who wants to better understand how our world situation has reached the point where we are now. In Bitter Lake’s more impressionistic format though, in its pauses and almost avant-garde musical junctures (as usual Curtis needle-drops everything from Nine Inch Nails to Kanye) there is more room for us to digest all this information, and let it trigger countless thoughts and associations, creating a bewildering but ultimately enriching viewing experience. There can be no doubt anymore that Curtis is an absolute master at what he does.

12. Force Majeure (Ruben Östlund)

Ruben Östlund’s tale of one Swedish family’s ski holiday from hell, an idyllic vacation turned into a soul-searching life-crisis, managed to make us nod, squirm and laugh nervously (often simultaneously) in the face of its painfully recognisable situations. At the same time it managed to sneak in serious, universal themes which make it a sort of arthouse version of Gone Girl: masculinity, self-delusion, the façades we put up even in long-term relationships. Here one simple event ends up tearing those down irrevocably and snowballing into interminable passive-aggressive bickering, going round in circles with hypothetical what-ifs, and even ‘contaminating’ the hapless couple witnessing our central couple’s original squabble into a sleepless, argument-riddled night of their own. (This then sets up a wryly hilarious final gag when the male of the accompanying couple feels the need to prove his own ‘masculinity’ in a coach.)

Sudden bursts of Vivaldi aside, there’s a cold neutrality to the style and pace giving Force Majeure a Michael Haneke-esque edge, that is if the Austrian maestro was endowed with a darkly biting sense of humour. Both the husband and wife come across as weak and terrible to each other, for different reasons, but there’s nothing we can’t relate to here nonetheless. Their resolution recalls John Ford’s ‘myth over fact’ policy to preserve the sanctity of the family unit when they shift their delusions onto their two children…

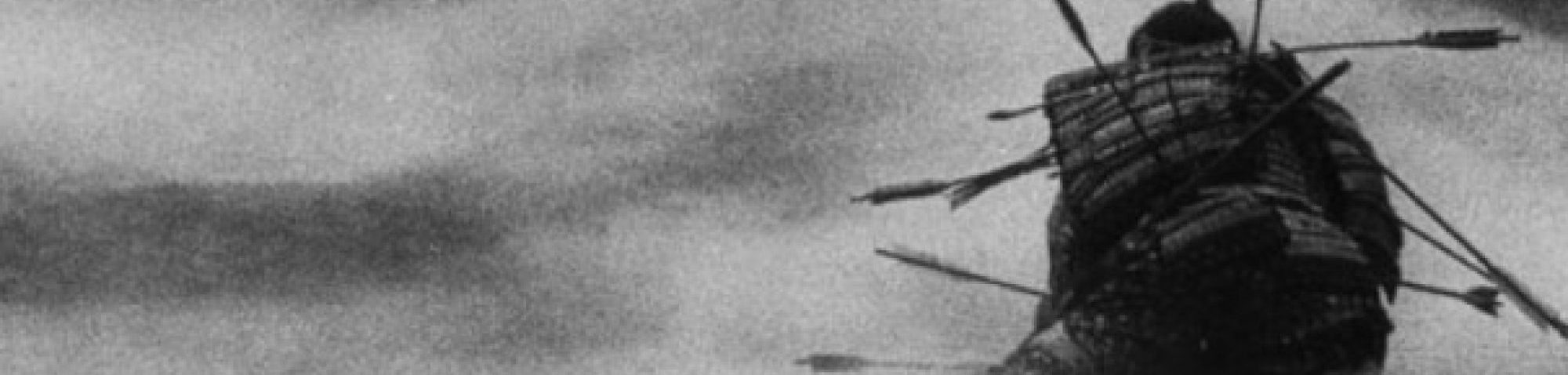

11. Aferim!

Radu Jude’s widescreen, black-and-white, 19th Century-set Western goes against the grain of what we expect from Romanian exports in the generation of Mungiu, Porumboiu and Puiu, and the contemporary realism of the New Wave. Not lost in Aferim! however is the Romanian coal-black humour, even with the more ‘exotic’ rural setting of Wallachia in 1835, and the subject matter of a local law enforcer and his teenage son together on the hunt for a runaway gypsy slave. The texture of the black and white film (as opposed to digital) photography and the slow pans showcasing the landscape (central to this being interpreted as a neo-Western like Jauja) impress and immerse, but it’s the naturalist acting and authentic script that make the film work as an exploration of past attitudes and how they may not have evolved as much as we’d like to think. Prejudices, across ethnicities and creeds, are rife (and often dished out in darkly humorous dialogue), making this already original look into the past, at a transitional moment of European history in the midst of Ottoman and Russian belligerence, also powerfully topical to the situation of contemporary Europe today.

List continued here: My Top 20 of 2015 (Part 2: 10-1)

I like these roundups – gives me a good list of what to watch as I’ve rarely seen any of them. However, I have now seen one of them – Force Majeure. What an excellent film. It’s stunning when you watch something like this how remarkably different it seems to someone used to Hollywood excess. The film depicts human relationships in such an insightful and detailed way that just never happens in US films.

I loved the whole premise of the film and the ending – this kind of parental charade was a clever denouement. Although, then the thing with the coach – wasn’t sure what that meant really, at least in relation to the main couple.

I think, besides showing the bearded dude’s hilarious attempt to prove his manliness, the scene is all about the wife still being high-strung from the first ‘catastrophe’ and fearing another one on the coach. It’s another scary scenario like the avalanche, but one that in the cold light of day was harmless in the end. In some way it’s a bit of a comeuppance for her, as this time it’s she who panics first and gets off the bus, and she is the one regarded as the panicky overreactor this time. There’s quite a few ways to look at the scene.