In no particular order, the films that still impressed me but not quite enough to fit into my top 20 that follows.

Personal Shopper (Olivier Assayas): A modern ghost story about mourning and mediums, from phones to psychics to personal shoppers, via the most powerful mediation tool of all: the human brain.

Things to Come (Mia Hansen-Løve): Isabelle Huppert as a philosophy teacher in a beautiful film about family, inter-generational relations and change, all in the key of Ozu.

Austerlitz (Sergei Loznitsa): Static shots of tourists visiting the site of a concentration camp act as springboard for us to meditate on important topics around history and how we think about it.

The Human Surge (Eduardo Williams): An experimental, globe-trotting film with three seperate threads on three different continents, loosely connected by a meditative outlook on the inter-connectivity of the modern world. There’s one moment in which we move from Argentina to Mozambique through the ‘portal’ of a laptop screen, in one seemingly unedited take, that is unforgettable.

A Quiet Passion (Terence Davies): With several moments of transcendent cinematic beauty, Davies’ biopic of Emily Dickinson clearly rhymes his own career’s concerns with the life of the great poet, making this a deeply personal ode from one introverted, underappreciated artist to another.

After the Storm (Hirokazu Koreeda): In several ways a return to Still Walking (2006) but also more of the same from the Koreeda of the last 10 years, which means warm, gently humanist family drama that leaves you feeling better about the world after watching it.

Hunt for the Wilderpeople (Taika Waititi): The only Waititi film I’ve ever really enjoyed and that largely thanks to a terrific Sam Neill as a grumpy grandpa stuck with an adopted 13-year-old boy, although a great synth soundtrack did no harm either.

Fences (Denzel Washington): Beautifully acted and heartfelt rendition of August Wilson’s play about the regrets and bitterness of one husband and father, and its ramifications on his family.

HyperNormalisation (Adam Curtis): Or how Adam Curtis predicted the Trumpageddon while the rest of us thought it was still a bad joke that couldn’t possibly come true.

What is the connection between a mysterious asteroid hurtling towards Earth, a strange Pandora’s box of unleashed forces which lure all those in its radius with promises of unlimited pleasure, a young woman seemingly engaging in a sexual act with a tentacle, and a violent homophobic attack on a male nurse who was beaten to death (the real-life event which director Amat Escalante read about and was induced into making a film by)? You’ll just have to watch this beguiling Mexican Tarkovsky-Zulawski hybrid of sci-fi, body horror and allegory to find out. In theory, The Untamed has no right to work, but yet somehow, strangest of all, it does and does so well enough to last long in the memory.

Cristi Puiu’s follow-up to the somewhat alienating Aurora (2010) is set over one family reunion that unravels into squabbles, breakdowns, and recriminations. Puiu has crafted an absurdist chamber drama, observed by a camera that pans across the cramped apartment’s rooms and doorways, listening to a medley of testy conversations in which relatives and guests argue over everything from 9/11 conspiracy theories to the legacy of Communism in Romania to Thai food. And speaking of food, in a gag Buñuel would have been proud of, the meal is perpetually delayed and the guests (who’d optimistically hoped to be done by 2pm) are ‘taken hostage’, be it by the repeatedly deferred arrival of a priest or more metaphorically by the memory of the late family patriarch whose death they are commemorating. People aren’t quite themselves on an empty stomach, and the stress and micro-aggressions of the diverse family relationships (which Puiu lets us gradually make sense of for ourselves as his narrative threads along) go from bad to worse. Amid all this mess our effective guide is Lary, doctor and elder son of the family, who strikes the perfect balance between sardonic detachment and inevitable responsibility, often a wry observer to the black humour in the rows around him, but eventually forced into being a player in the drama when he turns out to have a few revelations of his own…

A loose, inventive and playful biopic of Pablo Neruda (played by Luis Gnecco), the Nobel-prize winning poet, diplomat, and national icon in Pablo Larraín’s native Chile. It is 1948 and Neruda finds himself threatened with arrest for speaking out against the anti-Communist brutality of President González Videla (Larraín regular Alfredo Castro), and so begins a game of cat-and-mouse, between Neruda and police inspector Oscar Peluchonneau (Gael Garcia Bernal). At this point, fiction and imagination kick in. The movie is Nerudian, much like Soderbergh’s Kafka was a Kafkaesque film with Kafka as the lead character, rather than a straight biopic. Defying expectation, it splinters off into a labyrinth of different genres: policier, film noir, road movie, existentialist western. There is the sense that Neruda, depicted with multiple facets to his personality at different times, some likable and others far less so (Neruda’s friend Picasso would have approved of such a cubist multi-angled portrait), is in some way writing his own fictional cinematic autobiography as the film moves along, one which may be inspired by same the pulp detective novels we see him read. The hapless Peluchonneau, beautifully played as a blank slate (or should that be blank page) by Bernal, is totally committed to his job of capturing the great poet, but is he finally just a pawn in a larger literary game?

How to explain Bruno Dumont’s transition from serious Bressonite auteur to purveyor of slapstick absurdist comedy? With liberal imagination we could draw some connections to Dumont’s earliest movies (the working class of Northern France, an eccentric police procedural), but there’s no denying this is a totally different register he is working on at this stage of his career, a shift both unexpected and unexpectedly welcome. Equally enjoying themselves are trained thespians like Juliette Binoche and Fabrice Luchini shamelessly hamming it up in the role of inbred aristocrats, holidaying in a 1910s coastal town marred by a spree of mysterious disappearances. The two police officers charged with solving the case lie somewhere in between Laurel & Hardy and Vladimir & Estragon, the prime suspects are a local working class family who have a bizarre (and gruesome) way of treating the holidaymakers, and the surreal strangeness only takes off from there. That this comes from the same seemingly humourless director who brought us the nihilism-porn of Twentynine Palms (2003) only adds to the surprised hilarity.

In a world obsessed with perpetual growth and urban change (the word often used is ‘progress’), which takes no time to pause and consider, how can there remain any place for stability and reference points? The skyline of every major city is a configuration of cranes, and within a generation one can no longer recognise the location of foundational memories. Ackbar Abbas calls it the ‘deja disparu’ effect: before we’ve even had a chance to fully digest our environment it has mutated into something else.

In Kleber Mendonça Filho’s second feature, Sonia Braga gives a commanding performance as Clara, a widowed music critic who’s lived her life and her loves in the same apartment. It is the only apartment in the Aquarius complex yet to be sold to the property developers who increasingly apply pressure and bullying tactics, but still Clara won’t budge. Through immaculate directing and use of music, we get a rich sense of the life Clara has lived, and of everything she hopes to hold onto by fighting against the corporate greed attempting to snatch the physical anchor of her memories. This is a personal and political film, about the struggle between moral resistance and the corrosion of greed, quite literally corrosive in the film’s final metaphor, one that packs a cathartic punch.

More than ten years in the making, Homeland: Iraq Year Zero is an epic 6-hour documentary, made during filmmaker-in-exile Abbas Fahdel’s return to Iraq in 2003 to visit his family, and which was about as urgent as cinema got in 2016 in re-connecting with the human aspects of the world rather than abstract geo-political crises. Fahdel goes everywhere, films everything, with the pride and love of someone who has missed their homeland for so long, and finds in his subjects a general need to talk now that the regime has fallen and a weight has been lifted from their chests. Filmmaking as therapy, captured through Fahdel’s understated observational style. But Homeland is many other things too: a portrait of one family before and after the 2003 invasion; a general overview of the mood in Iraq through various interviews, snippets of television or radio, and other tangents like a visit to what’s left of Iraq’s film archive; a city symphony dedicated to Baghdad’s streets and markets; and a heartbreaking examination of the role of the camera as witness.

With just three films (You Can Count On Me (2000) and Margaret (2011) were the previous two), acclaimed playwright Kenneth Lonergan has developed into one of the most astute creators of quietly devastating character studies in American cinema. This one may be his best yet, focusing on a small Massachussetts community in the midst of a cool winter whose icy light all the better illuminates the trauma thawing within its denizens. Into this setting returns Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck in an impressive performance of desensitised emotional damage with just enough bitter humour to make his character constantly watchable through the pain). And pain is what he revisits, literally as Manchester-by-the-Sea is where a certain life-changing incident left him damaged forever, and figuratively as flashbacks gradually reveal the details, culminating in the central scene of the film, almost too emotionally intense to watch and scored to Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor. By the time of the revelation of the reason Lee is barely subsisting through a numb existence of self-hatred, we still feel invested in the characters, and Lonergan succeeds beautifully in his depiction of broken hearts trying to keep beating, and of life going on.

This is the Coen Brothers’ tribute to what André Bazin called “the genius of the system”, that ineffable magic permeating the Hollywood movie factory, giving life to its conveyor belt of classic after classic in every genre. As a movie set on movie sets, Hail, Caesar! lovingly sends up just about every one of these genres from the singing cowboy (which the Brothers would revisit in Ballad of Buster Scruggs) to Busby Berkeley musicals (Scarlett Johansson as a mermaid in the middle of a large scale synchronised swimming sequence), via Ophulsian melodrama, Carmen Miranda numbers, and many more. Bliss for any nostalgic cinephile, this bygone era is recreated through the very magic of the cinema it represents, the world of the studios here alive with all its power struggles, backroom machinations, gossip scandals, blacklisted screenwriters, and kidnap plots gone wrong (well it is the Coens after all). Finally the film leaves us with themes more profound than they may at first appear. As ideology and religion clash for the monopoly on Truth, one man makes the more modest choice to bank on 24 illusions per second, a less insidious kind of truth but a truth nonetheless, told through the medium of light in grandiose movie theatres — which we’ll hopefully be getting back into soon.

Speaking of Bazin, it was his firm belief that the essence of filmmaking was the camera’s ability to reproduce the reality in front of it. But behind the indiscriminate lens lies the subjectivity of an observer and an aesthetic perception. Over a 25-year career as a cinematographer, Kirsten Johnson has spent so long recording the reality in front of her with a camera that she calls this mosaic-film, made up of scenes and outtakes from other films she’s worked on, her memoirs. Images from Bosnia, from Nigeria, from Afghanistan, from Brooklyn, and many other places, are here assembled into a stream-of-consciousness with the occasional personal foray into Johnson’s family life. That she films her mother during her last years as Alzheimer’s fades her memory away is apt to the film’s project: a meditation on the camera’s ability to create memories and to share them, in a globe-trotting decade-spanning visual manuscript. After all, the original camera operators were the Lumière employees sent around the world with ‘cinematographs’ that were both camera and projector, technologically able to both record and show images.

Cameraperson also stands as testament to visual curiosity of Johnson and every intrepid cameraperson, searching for some truth with their lens, be it about the Balkan bloodshed or the horrific murder of James Byrd Jr. As time is captured, it nonetheless keeps on flowing, Johnson and her family change, new unexpected memories are formed; as Jacques Derrida pops up to say in one of the film’s vignettes: the cameraperson is like the philosopher who falls into the well for being too preoccupied looking at the stars.

If hospitals and ambulances abound in Romanian New Wave films, it is that their state-of-the-nation diagnosis is clear: entrenched corruption at the heart of Romania’s institutions is the deep-rooted malady that has stifled post-Ceausescu hopes into powerless anger. As in Sieranevada, the protagonist of Graduation is a doctor, Romeo Alda, whose ethical dilemma is the focus of the film. On the day before his daughter Eliza’s final high school exam, the result of which decides whether she can go study at Cambridge, she is sexually assaulted in the street. The trauma of this event leaves Eliza far too shaken to focus on the exam, and anyway her leaving Romania for the UK seems to be more her father’s obsession than her own… Hence Dr Romeo is left with a stark choice: should he make use of the network of mutual back-scratching connections to ‘alter’ Eliza’s grade so that this traumatic incident does not change her trajectory, or should he ensure that the very same moral principles he finds lacking in Romania are at least preserved in his family unit, even if it ironically means his daughter must stay in the country he so wants her to escape from?

Cristian Mungiu had already shown with 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days his skill in creating suspense out of unexpected subject matter, and his follow-up to 2012’s Beyond the Hills is more of the excellent same, building on the Romanian New Wave credo (as ever Vlad Ivanov appears, this time as a police inspector Romeo went to school with) while adding a touch of Haneke’s Caché and Martel’s The Headless Woman. Like those films, this is among other things a portrait of guilt, responsibility and hypocrisy. The film’s perspective remains very close to Romeo’s throughout, so we have to pay extra attention to spot the things that he is wilfully blind to. Watch for the number of times Mungiu meticulously trains our eye to focus on the centre of the frame, only for potentially crucial information to appear on the edges: be it the clues to who might have been a witness to the assault on Eliza or the mysterious attacker throwing stones at Romeo’s windows and windshield throughout the film.

Reminiscent of the metaphysical temporal fluidity of the Iranian 2013 single-take film Fish and Cat (Shahram Mokri), Bi Gan’s indelibly moody and cyclical debut feature was ostensibly about a small-town doctor searching for his missing nephew. But on a more visceral level it combined Buddhist philosophical undertones and poetic elements of magic realism with a bravado technical tour-de-force: an incredibly elaborate hand-held and perfectly choreographed 41-minute long-take that loops and winds in on itself and in which past and present seem to co-exist. The result dazzles the viewer with a meditation on memory and loss, which for all its dream-like qualities remained firmly rooted in real emotions and a very specific sense of place — the city of Kaili and the Miao community. Worth mentioning in passing that Bi Gan has since outdone himself in the technical stakes with a one-hour-long single take, that floats and weaves in 3D no less, in his second feature Long Day’s Journey into Night.

A lonely retired father in Germany, who keeps himself amused by playing haphazard pranks on anyone willing to indulge, pays a surprise visit to Romania, where his workaholic daughter who never has time for him is based. At first intending to merely combat loneliness, he eventually decides to teach her his own kind of homespun wisdom: a life beholden to the petty superficialities and power-games of the business world and without any fun or spontaneity is no life at all. It could be the plot of a warm-hearted Frank Capra screwball comedy, but German director Maren Ade infuses Toni Erdmann with a style and mood that sits alongside the Romanian New Wave’s deadpan mix of serious and hilarious (again, there’s a small part for Vlad Ivanov).

Ironically, for this dad to infiltrate his daughter’s life and the corporate bullshitters around her, he himself has to take on another persona, in essence becoming a kind of modern-day Boudu bringing mild anarchy into the bourgeois business world, to nobody’s greater dismay than the daughter herself — the only reason she initially goes along with her father’s games instead of revealing his identity to colleagues is because of what it would cost her own face value. A comedy of manners then, one that’s constantly entertaining, as well as a moving father-daughter story, and also an allegory on corporate politics and globalisation.

Did this sensuous, mood-driven character study of a young gay African-American man searching for identity and self-acceptance really win the Best Picture Oscar and gross more than 15 times its budget at the box office? Yes, no need to pinch yourself, this really happened, and all in the midst and mist of the rise of the Trumpageddon, no less. Like several films in this top 10, Moonlight provided a much needed counter-shot of the USA, a tonic from the dismay of the political machine, and an empathetic look on people at the margins of society. Here, drug-dealing kingpins are afforded a refreshing humanity, and a sensitivity is used to depict the interior life of a taciturn boy (then adolescent, then man) caught within a system where violence and lack of opportunity is a cycle — characters whose internal lives are rarely dealt with so integrally onscreen, if indeed ever represented at all. On top of this this, Jenkins’ triptych was sensual cinema, conveying the mood of its moments through use of shallow focus, the sounds of the ocean, the reflections of light on skin, the fluid choreography of its camera movements, all building into an immersive immediacy.

Religious differences force a Puritan settler to break away and drag his family along as outcasts in the New England wilderness — the beginnings of the American pioneer myth but soon to be turned on its head. This is a man who presumably sailed away from England because he didn’t see eye to eye with the Church there either, and by that logic thinks he and his family are the only remaining true Christians on God’s green Earth. This captures some of his stubbornness, though he’s painted not as a tyrant but a man trying to do what he thinks right according to his dogmatic beliefs. It is these beliefs which are brutally challenged, not just from the difficulty of surviving alone far from all other settlements, but more ominously in the form of his teenage daughter who is undergoing an adolescent identity crisis, who may or may not be responsible for the sudden disappearance of her baby brother, may or may not be in some unholy pact with the family’s black goat, may or may not be a member of a coven of witches. A horror film with a visceral sense of bringing the past back to life and an incredibly well-maintained atmosphere of enigmatic dread, The Witch marked Eggers as a filmmaker to follow closely.

Jarmusch’s cinematic haiku stars Adam Driver as a bus driver called Paterson, in the town of Paterson, New Jersey, who writes poems in between bus routes and whose favourite poem collection happens to be Paterson by William Carlos Williams. The film’s low-key narrative takes place over one week and is anchored in his daily routine, his job, his interactions with his wife Laura (Golshifteh Farahani), herself a fount of idiosyncratic creativity, and in the way he incrementally constructs his poetry on the basis of the tiniest observations he makes, the people he meets and the snippets of conversation he overhears. As well as an ode to the town of Paterson itself, this is a film about remaining open to the possibility of being inspired by the world, with its observational camera constantly picking up our protagonist’s quiet way of looking at things, in which anything can be a source of small joy. It is clearly also telling (and no doubt there is some of Jarmusch in this portrait) that Paterson the character is completely averse to the attention-sapping ubiquity of smartphones, instead tapping into a kind of mutual radar through which like-minded ‘poets’ (whether they actually write poetry, rehearse raps in a laundromat, or translate their inspiration into home design and cupcakes) all seem to recognise each other throughout the film. It’s contagious enough to make you want to go out and look at things around you afresh, and let the daily transience of the world continue to surprise you with your own chance encounters and moments of epiphany.

Not being particularly fond of Scorsese’s Di Caprio collaborations, I was more looking forward to this long-gestating adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s novel about two Portuguese Jesuit missionaries marooned amid the anti-Christian persecution of 17th century Japan. However, perhaps predictably for a 2.5 hour film filled with theological debates regarding the rights or wrong of Christianity trying to take root in a country with its own rich culture and religious traditions, Silence endured a somewhat muted reception. But this is a beautiful, grand, and deeply felt film. Though ever-aware that Christianity as institution represented one branch of colonialism, it makes us feel the blind leap of faith required by individuals in their travelling to the other side of the Earth to grapple in the dark for any shred of meaning in their mission. Yet all they seem to be doing in Japan is exacerbating the torture and deaths of peasant villagers. Visually, their blindness and deafness to any concrete sign of God’s encouragement is evocatively translated into dark empty caves and painterly interiors where the flame-lit bronzes and coppers of the character’s faces are surrounded by total blackness.

Andrew Garfield (Padre Rodrigues) and Adam Driver (Padre Garupe) are the two leads. With Paterson and this, Driver was already becoming one of the finest actors of his generation, but Garfield has the greater challenge here: showcasing Rodrigues’ empathetic humanity with moments of weakness and believable sincerity. At times Garfield’s idiosyncracies recall Willem Dafoe’s dazzlingly human Jesus in Last Temptation of Christ, although for all Rodrigues’ messiah complex it is Driver’s Garupe, more solemn, less willing to compromise, who dies a martyr’s death. And speaking of idiosyncratic, the ‘villain’ of the piece, Inoue, the local Inquisitor ordering the torture and persecution of the Japanese ‘Kirishitans’, is played by Issey Ogata (from Edward Yang’s Yi Yi among others): not a man you cast if you’re looking for a conventional actor’s performance. Despite being spoken of with reverent terror, when we finally meet Inoue he arrives on the back of a donkey wearing an oddly beatific grin, and speaks his parables in nasally high-pitched plosives. This bizarrely chilling Inquisitor is one of many memorably crafted characters in a film that will continue to grow in reputation as a late masterwork in Scorsese’s filmography.

The Demons, the Canadian debut feature by Quebecois writer-director Philippe Lesage, is a strange coming-of-age story, centred on 10-year-old Felix and his interiorised fears generated by misapprehension of the adult world encroaching around him. This has been done before, from Cria Cuervos to Spirit of the Beehive to The Reflecting Skin, but never quite like Lesage does it here. He sustains a glacial mood of dread, through clinical camerawork, even in the most innocuous of scenes. Dialling up an ominous orchestral score over documentary-like observational wide shots of Felix with classmates in the playground or at the swimming pool, the anxiety becomes palpable: is something going to happen? What is going to happen? Elsewhere, Lesage deliberately places the camera at low height to block out what certain characters are doing — all things that set up subsequent pay-offs later in the film, although not quite in the way we might have expected.

In dealing with Felix’s array of different concerns, from his confused and confusing awakening sense of sexuality, to the ferocious quarrels of his parents, to the rumours that a child murderer is on the loose, the film remains episodic and refuses any strict cause-and-effect relationship as it moves from sequence to sequence. It leaves the film feeling unmanipulative, open to our interpretation and thereby respecting its audience, even as it becomes genuinely unsettling and shocking. And yet the film is also rich enough in its depiction of childhood to have moments of real sweetness in there too, especially in Felix’s relationships with his two siblings.

Moving from the Oregon pastures of her previous features, Kelly Reichardt’s triptych (adapted from three short stories by Maile Meloy) relocates to a Montana setting no less germane to her observational style. Equally, the short story format is a perfect fit for her creation of worlds and characters through suggestive broad strokes of small details, routines, and gestures. In the first of the stories, Laura Dern is a small-town lawyer frustrated by a client who rejects her advice, and yet in her stoically resigned way will end up going beyond the line of duty for him.

The middle story is quieter, with Michelle Williams as a wife increasingly alienated from a husband she finds incompetent, and out of touch with her teenage daughter. To compensate for her inauthentic familial relations, she seeks to build the most authentic family house possible, a quest which will lead her to asking an awkward request of a frail elderly man played by erstwhile Robert Altman regular René Auberjonois.

But it’s the final story that really steals the show, and packs the biggest emotional gut-punch, as Lily Gladstone’s ranch stable girl builds a crush on night-school law teacher Kristen Stewart. As a whole, Certain Women creates a subtle fabric of thematic connections across its characters, each wanting to be listened to yet unable to communicate what they feel to those around them, and always still ascribing great emotional value to seemingly inconsequential things: receiving a letter, a pile of old stone, or a wordless horse ride to a diner. If Meloy’s stories surely recall the great Raymond Carver, maybe it’s time to say Reichardt is the much-needed heir of the sensibilities of Robert Altman, who famously adapted Carver’s stories in Short Cuts — even as she is a minimalist to Altman’s maximalist, she too is a maverick working by her own rulebook, reinventing genre conventions, and casting a sympathetic eye on characters on the outskirts of American society.

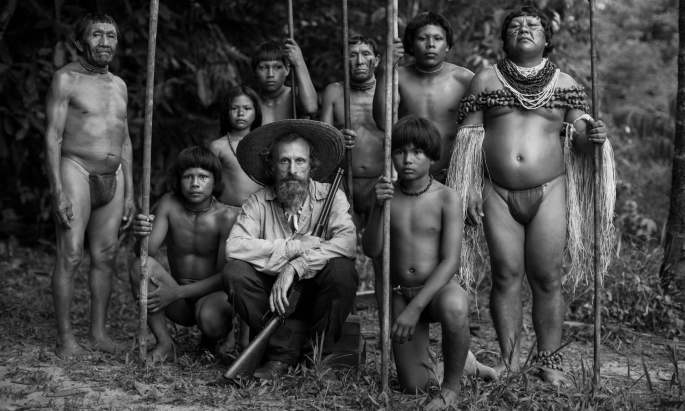

In 1909, a German ethnographer falls gravely ill during his research expedition through the Amazon and is told that only an extremely rare plant called the yakruna can cure him. In the early 1940s, an American botanist has been sent to the Amazon by his government to research the properties of this same quasi-mythical plant. In both cases, the white men seek guidance from the Indigenous shaman Karamakate (played by Indigenous non-professional actors Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolivar in his 1900s and 1940s incarnations respectively). Two cultures and two temporalities thus collide, in two quests upriver through the jungle, through the perilous terrain of a nature that must be respected at every step, through the insanity and violence sowed by colonisers and rubber barons. The film moves between and connects these two timelines through the osmosis of dreams and premonitions, all in gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, at least until the screen explodes into a fantastical psychedelia of colour.

The younger version of Karamakate especially, with dignified poise and muscular body, covered merely by a loincloth and a majestic necklace, conjures the iconography of the Noble Savage. But this is a film going far beyond those stereotyped ideas, showing how both sides have a need to learn from each other, transgressing cultural boundaries to arrive at knowledge untainted by ulterior motives. Those who seek the yakruna for personal or economic benefits are doomed to failure. As the fear of climate apocalypse rises in our contemporary world, more than ever do we have lessons to learn from peoples who have lived in harmony with nature for thousands of years. Ciro Guerra’s film rescues these memories in an Amazon that tragically probably no longer exists, and does so with all the beauty of a monochrome daguerrotype plate crystallising a moment in time.

Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama is a film better first watched knowing as little as possible going in. Its first 40 minutes are a methodical procedural, in which a cohort of French youths, six young men and two young women, of varying class and ethnic backgrounds, criss-cross around the streets and metro of Paris with a meticulously synchronised precision. The mesmerising abstract slickness of this opening act, almost wordless, raises questions: who are they? What are they doing, and why? Some answers are slowly revealed, as pieces of a jigsaw coming together through flashbacks and intersections. Others are never quite made clear, but the film is never any less compelling for it.

If this first part clearly recalls Elephant, Alan Clarke’s experimental treatise on violence with its formalised camerawork and sense of detachedly following cipher-like protagonists, the ensuing part of the film is more of an update on what George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead did for consumerist culture in the 1970s. The group of youths are now holed up inside a luxury department store in central Paris, whiling the time away as they wait out their long day’s journey into night. This setting, a windowless cocoon of high-end brand goods and faceless mannequins partially filmed at La Samaritaine, is the perfect Rorschach test for our ambivalent feelings towards this enigmatic film’s band of characters. As time ticks on, now more slowly than the relativistic synchronisation of the first part, they wait for a dawn which they hope will come but which we increasingly know never can.

While Bonello offers no specifics, no socio-political lecture, no concrete answers, he remains intelligently aware of the divisive, provocative nature of his filmmaking, but with bravado and tour-de-force technical control he walks the tightrope between dangerously topical and uncannily abstract. The film’s dreamlike images and sounds provide all the answers we need, even if it be on an unconscious level. As ever with Bonello’s films the soundtrack is full of memorable needle drops, reappropriating songs we’ve heard before to make them sound strangely anew. Blondie’s ‘Call Me’ provides the backdrop for a euphoric trance-dance as the end is nigh; a rendition of ‘My Way’ by Shirly Bassey is lip-synced by Yacine, one of the young males of the group, in full make-up in a performance that takes on the dimensions of a defiant swansong; and John Barry’s synthy and jazzy heist-appropriate theme tune to The Persuaders stops and starts over the film’s chilling conclusion. And then there’s the momentum of Bonello’s own woozy synth soundscapes, complementing the often dream-like images: Yacine finding and staring at his mirror mannequin modelling his exact same outfit from tip to toe; Mika, the youngest of the bunch, wearing an expressionless golden mask, shortly before he has a particularly eerie nightmare which Bonello edits to perfection; or David, one of the more affluent members of the group, wandering out into the deserted streets of Paris while cars burn around him.

In his press tour following First Reformed, Paul Schrader has often repeated that a great film starts as soon as you walk out of the theatre, at which point it begins to live its afterlife by ringing through you like a bell being struck. The memory of Nocturama hasn’t stopped vibrating inside me since I saw it three and a half years ago.

5 thoughts on “My Best Films of 2016”