Films reviewed:

Paths of Glory (1957)

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Video essays:

2001 A Space Odyssey

A Clockwork Orange

Full Metal Jacket

![]() Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power, And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave, Awaits alike the inevitable hour. The paths of glory lead but to the grave. — Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”

When it comes to self-criticism of the (powerful and censorious) French military, and despite Wooden Crosses‘ allusion to the callousness of the officials, French cinema hasn’t the greatest track record. A full-on assault of the injustice of the military institutions was left to this, Stanley Kubrick’s calling card to what would be a short-lived Hollywood studio career. Paths of Glory represents a move away from the anti-war pacifist film (e.g. Renoir’s Grand Illusion which still maintained a nostalgic vision of soldierly decorum) toward the outright anti-military — it proffers a profound distaste of the rigid authoritarianism, political machinations, and hypocrisy of the system’s hierarchies, a distaste which Kubrick would famously push to even more grotesque extremes in Dr. Strangelove.

Like many a courtroom drama, the battle is between noble idealism and compromised pragmatics — a duel replayed, with the same outcome, in Joseph Losey’s 1964 King and Country where Tom Courtenay is an English soldier awaiting to be court-martialled for desertion in a WW1 trench, and Dirk Bogarde his makeshift defence attorney in a kangaroo court. While Losey eked every bit of mise-en-scene and camerawork out of his claustrophobic setting, Kubrick’s film is famed for its expansive tracking shots propelling us with these men into the cul-de-sacs that can only ironically be called ‘paths of glory’. Amid all the injustice, Kirk Douglas is a beacon of Enlightenment values and weary compassion as Colonel Dax, who refuses to back down before an institutionalised injustice willing and eager to sentence three men to death, simply for the offence of refusing to be cannon-fodder. The twisted nature of this war’s catch-22 comes into full view; the only choice a soldier has is how to die, whether from enemy machine guns or a firing squad of countrymen. That the French banned it for twenty years speaks volumes. (December 2018)

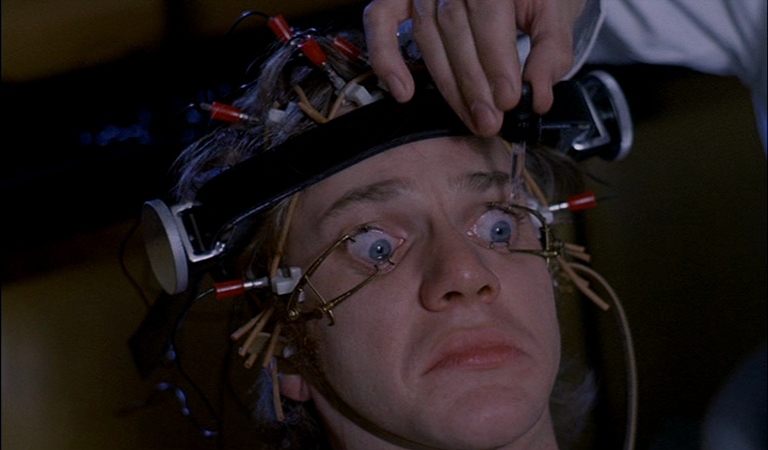

![]() A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Some years ago, I was a postgraduate student at Brunel University. On the first day wandering around my new campus, I was struck by a sense of deja vu by one building. Amid a campus-wide architecture of Brutalist concrete, this one had a particularly weird arrangement of blocks, like some Cubist rendition of the Easter Island statues. But it was not an architectural connection I was feeling, it was a memory, despite never having been here before. I only finally put my finger on it thanks to a Professor sharing it as a piece of trivia: this building had a cameo as the Ludovico treatment facilities in A Clockwork Orange. A decade or more after my last viewing, there was clearly something about the architecture, the visuals, the texture of Stanley Kubrick’s film that had stayed within me, even if unconsciously.

When all is said and done on the controversy around the film’s violence (let’s face it, pretty tame by today’s tolerance levels) or of the merits of its rather shallow status as a beacon of counter-culture cool — yes I too, dear readers, will confess to having once purchased a Clockwork Orange poster from Camden market during my teenage years — when all of that extraneous reputation is said and done, when the teenage infatuation is cured alright, Clockwork Orange remains a cinematic monument because stylistically there had been and has been nothing quite like it. Kubrick knew that in an ocean of cultural uniformity, for a film to stand out it had to first be interesting aesthetically.

So he used every asset at his disposal to create stylistic frissons: the wide-angle lens cinematography giving everything an off-kilter look; the costumes that have since become iconic; the use of slow-motion, pop-art montages and sped-up up shots giving the film an almost experimental style at times (inspired by Kubrick’s viewing of Japanese new wave cinema as I show in my video here); the contrast of performances between McDowell’s expressive, almost cartoon-ish young rebel and the British character actors exhibiting restraint around him; the euphoric symphony of Beethoven or Rossini or Wendy Carlos’ electronic arrangements on the soundtrack; and yes, Kubrick’s judicious choice of locations to anchor the film in real settings that were a vision of what the future might look like from the perspective of 1971.

But, I hear you judiciously ask, is this not just style for style’s sake? Re-viewing this film now slightly older (and hopefully wiser) than my teenage self, I am inclined to disagree. Form and content do match here. For several reasons, style is actually part of what the film is about. This is a film about stylistic frissons, just like the ones Alex feels whenever he hears Beethoven, about Alex’s Stendhal syndrome being the only bastion of humanity within him, about his response to the aesthetic of musical art making him a man, an orang, and not a mechanical automaton. (A note on the title here: the novel’s author Anthony Burgess spent formative years in then-colonial Malaya and loved wordplay; I think we can safely assume the ‘orange’ of the title is a play on the Malay word ‘orang’ which means man, as in ‘orang utan’ the old Malay term meaning ‘human of the forest’.)

In this alternative society the film conjures up, one not quite in the future but somehow at a slant from the present, where the big functionalist architecture like that Brunel building stands in for both the visual style of an exotic future and a dehumanising rigidity, Alex’s nature (however heinous it may be) comes to represent a lone island of human-ness, in all its ugliness and beauty. Beauty? Yes, for an inextricable part of Alex’s nature is this aesthetic sensitivity he feels, the way the hairs on his skin stand up when he hears music, and uncontrollably he is forced into his very own and very unique response. This response is an innate part of what makes him him, and of what makes him human. Alex is not cultivated or cultured, he hardly attends school and we can safely assume has no background in studying classical music: yet his instinctive response to the music he loves is overwhelming and it is his alone. Style and aesthetic can elicit this response, and that response is the one humanising factor of Alex’s character — it is when the Ludovico treatment accidentally takes away this response to Beethoven’s music, making him associate it with all that should make him ill, that we understand: when losing his free will, Alex has also lost his aesthetic sensitivity, and hence what makes him human.

The film (and of course Burgess’ source novel) asks big philosophical questions about nature vs nurture, and even if I tend to disagree with Kubrick’s stance (I think he sides more towards nature while I am more towards nurture), the film does offer a rich fount of possible discussion. If Alex’s intrinsic love of music is part of his very core every bit as much as his inherent violence, as seen by how the Ludovico treatment ends up yoking the two together, then removing his violent instinct by force is equally as dehumanising as stunting his love of music. Once one is gone, so too is the other. Both make us human and both must be faced: the cultivated ‘beauty’ of sublime music and the deep-rooted history of violence within us. If the human species could ever transcend its evolutionary history of violence through such methods, deprived of free will and choice, would that be justifiable? Or can we overcome our own nature through other means? Big questions which relate to one of Kubrick’s pet themes which he deals with here armed with a fitting stylistic bravado: the question of what it means to be human and what it means to be de-humanised.

Certainly, then, A Clockwork Orange is thematically related to 2001 A Space Odyssey, the film Kubrick had made before. And in terms of narrative structure, we could make it part of a loose trilogy with Barry Lyndon and Full Metal Jacket: all three films have a picaresque structure charting a young man’s (Alex, Barry Lyndon, Private Joker respectively) journey through highs and lows, rises and falls, violence and dishonour. And all three have a three-act structure: in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (which famously left out the final chapter of Burgess’ UK edition of his novel in which Alex truly changes), Alex in Act 3 (post-Ludovico treatment) ends up exactly the same as Alex in Act 1 (pre-Ludovico treatment). So goes Alex’s rehabilitation in Kubrick’s cynical and cyclical view. So too, my dear droogs, should this film be viewed after decades of sensationalist controversy and teenage idolatry for what it really is: a fine yoking of style and theme by one of cinema’s greatest aesthetic masters. (August 2023)