There comes a time in life, usually in the critical apprenticeship phase of childhood, when we come to realise the world we once thought simple, ordered and relatively benign, is actually anything but. We discover that, on a large scale, humans scarcely adhere to the rules and values adults had preached to us (good manners, discipline, fairness and whatever else), and in fact have turned the world we live in into a complex, brutal and perhaps irretrievably broken place. No going back after that; the pieces cannot be put together again.

Some of us choose to accept or ignore these fissures. Some live in denial and pretend all is fine, that the pieces are still intact. Others still try to recreate replicas of the world as they once thought it to be (this includes many artists and filmmakers, with mixed results). Then there’s those who try to make sense of the whole damn mess, who seek the connections at the heart of what makes this giant chaotic system of ours tick, and try to put a few of the pieces back together somehow.

Among these, we surely encounter the odd charlatan and lunatic conspiracy theorist. But there’s also a few with a vision more poetic and insightful, who have a higher vantage point than the rest of us. One from which they’re able to play some cosmic game of connect-the-dots, and form an atlas of sorts revealing links and connections. It’s the equivalent of clustering together a few jigsaw pieces of a 10,000-piece puzzle, even though several thousand more are missing. Borrowing their view, at least for a very brief moment, we once more glimpse a faint recollection of that long-lost method behind the madness.

Scientists and mathematicians do this all the time, searching for patterns and order in the observable world and building theoretical frameworks in which to slot natural phenomena. Writers as diverse as Herman Melville, John Dos Passos, Umberto Eco or Thomas Pynchon all did it in the grandiose scale of their writings. Sergei Eisenstein did it, creating associations between all kind of disparate things through his intellectual montages. So did Jean-Luc Godard, who sees connections in everything, threading together pop culture, linguistic theory, the Vietnam War, Humphrey Bogart, Existentialism… and that’s even before his really radical phase.

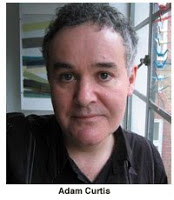

To this list of great connectors, another name may be quite uncontroversially added: Adam Curtis. For 30 years, Curtis has been making documentaries, primarily at the BBC, weaving together unexpected connections into vast tapestries. His films are unique explorations of history, power, society and ideas, and the interstices within which they all meet. Certainly these are vistas over a macro-scale, which is far from the only way to see the world, but they are among the most thrilling and dizzying efforts of their kind.

They are dizzying for the sheer amount of people, ideas and events (many which we might have safely assumed to be independent and isolated) they yoke together in surprising ways. What’s thrilling is when Curtis makes the connection fall into place and it all clicks together, opening up in our thoughts a mental picture of the modern world as an inter-connected web of factors, influences, actions. That’s the brief glimpse I mentioned earlier.

In The Living Dead (1995), a line is drawn between collective memory and history, specifically that of WW2 and the Cold War, and the rhetoric of Thatcher/Reagan era politics. In The Century of the Self (2002), Curtis laid out a history of public relations, advertising and mass consumerism originating in the theories of Sigmund Freud, which his nephew Edward Bernays then applied towards selling a myth of individualism. Curtis goes further and ties everything up by linking it to the new Clinton/Blair style democracy of the 1990s.

The connections were no less wide-reaching in The Power of Nightmares (2004), where the rise of radical Islamism and Al-Qaeda, was juxtaposed with that of neo-conservatism in the US, their mutual relations seen as impacting each other in unexpected ways. And, most complex of all, were the ideas associated together in All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, probably Curtis’ most ambitious film in scope. All manner of things from the internet, stock markets, evolutionary game theory, ecological systems to Belgian colonialism, are assembled into a vertiginous treatise on how dreams of what the computer would achieve for mankind backfired with unanticipated consequences.

Curtis joins up these big ideas using his trademark mix of stock footage, archive finds (many of which are fascinating in their own right), interviews with pertinent talking heads, effective soundtrack choices ranging from Leonard Cohen to Nine Inch Nails, all punctuated by narration from Curtis himself and his signature title-cards. It takes great skill to bring together so many disparate elements in a rewarding way, and Curtis is certainly a tireless researcher and far-seeing historian of ideas. But more than that, he is also a fantastically gifted story-teller. You might be initially dazzled by the multitude of information thrown at you by any of his documentaries, but you’re never less than riveted by the yarns he spins, nor are you going to leave without at least one great anecdote you’ll want to share.

This story-telling ability gets at why we so badly need his films, in a mediatised era when simplistic stories and imagined realities are constantly propelled at us from all directions (precisely tapping into that nostalgia for a lost past where things were as straightforward as good-evil dichotomies). As Curtis himself implies in some of arguments, we have become somewhat bored and jaded, due to the failures of previous generations to successfully create change in the system — whether that was ever possible anyway is another question, but certainly there has been a loss of idealism giving way to cynicism where faith in the possibility of progress has all but drowned amid postmodern dispassion.

Equally numbing is the growing sense that the political process is governed by a self-serving clique’s desire to maintain the status quo, shrouded by lies and corruption, and so removed from the real day-to-day experience of most people as to not be worth paying attention to anymore. Hence vast disengagement and disenchantment. The way to make us rekindle our interest in what’s happening on the bigger picture, and remind us how it affects us all, is to translate it into engaging stories, that can entertain us, inform us and make us care again about trying to make sense of the myriad events in our world.

Curtis traces some of these unpredictable, chaotic events retrospectively, showing countless times how the opportunism of those in power only ended up contingent to unexpected side effects. Indeed one of the recurring lessons here is how randomness often comes back to bite those who think they knew better, be it the CIA’s foreign interference, European colonisers in Africa or the technocrat-utopians who revered the philosophy of Ayn Rand, all with catastrophic results in the end. Curtis is the ideal man for the task of mapping all this out, thanks to his understanding of the non-linear path taken by history and the evolution of ideas, be it the idealistic of those who once thought they could create a better world, or the cynical pragmatism of forces wanting to manage the masses through consumerist technocracy. Curtis documents it all brilliantly.

However, we should not lose sight of the fact Curtis is a story-teller, a creator of meta-narratives to rival those more simplistic ones. Yes, he grabs our attention by shining light on oblique trails and angles, giving us possibly a better framework for making sense of the world around us. But there is no such thing as absolute objectivity in film, not even in so-called documentaries, which as Godard once said always tend towards fiction anyway: an engaging documentary is also a good story well-told. It is best to see Curtis’ films as food for thought, or as a launchpad for research of our own. For this reason, his films are essential viewing, a perfect impetus to make us reconnect to the world and try to piece part of the jigsaw back together for ourselves. Not that we’ll ever recover that long-lost blissful simplicity again, but at the very least we’ll sneak a clearer view of the complex inter-connectedness underlying everything around us.

Adam Curtis’ new film and also his most experimental and loosely structured, Bitter Lake, recounting the history of Afghanistan and its strange relation to the West, can be watched exclusively on BBC iPlayer here.

The majority of his earlier films are available to view online here: http://thoughtmaybe.com/by/adam-curtis/

His blog is here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/adamcurtis

Wow! Best review of the work of Adam Curtis you’re ever going to read. So many, standalone, literally perfect paragraphs, this one won me over by the merest fraction: “Some of us choose to accept or ignore these fissures. Some live in denial and pretend all is fine, that the pieces are still intact. Others still try to recreate replicas of the world as they once thought it to be (this includes many artists and filmmakers, with mixed results). Then there’s those who try to make sense of the whole damn mess, who seek the connections at the heart of what makes this giant chaotic system of ours tick, and try to put a few of the pieces back together somehow.”

I’m in the category of trying to make sense of the whole damn mess, working to try and create a solution too. Think the author of this article is similar